“Every part of all this soil is sacred to my people. Every hillside, every valley… has been hallowed by some sad or happy event in days long vanished.” (Chief Seattle)

“Every part of all this soil is sacred to my people. Every hillside, every valley… has been hallowed by some sad or happy event in days long vanished.” (Chief Seattle)

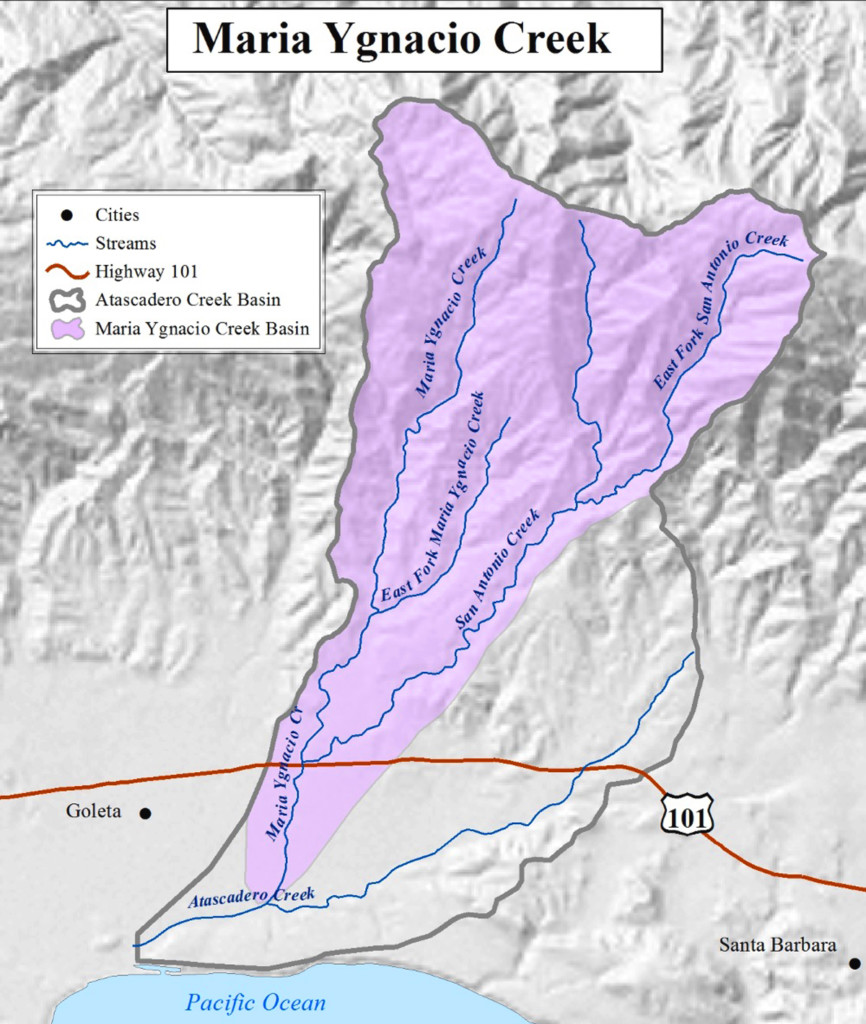

Driving north on Highway 101 between Turnpike Avenue and Patterson Avenue, there’s a small and simple sign on the side of the road that reads, “Maria Ygnacio Creek’. Thousands of people pass it by everyday, but very few see it. In fact, if you blink you’ll miss it.

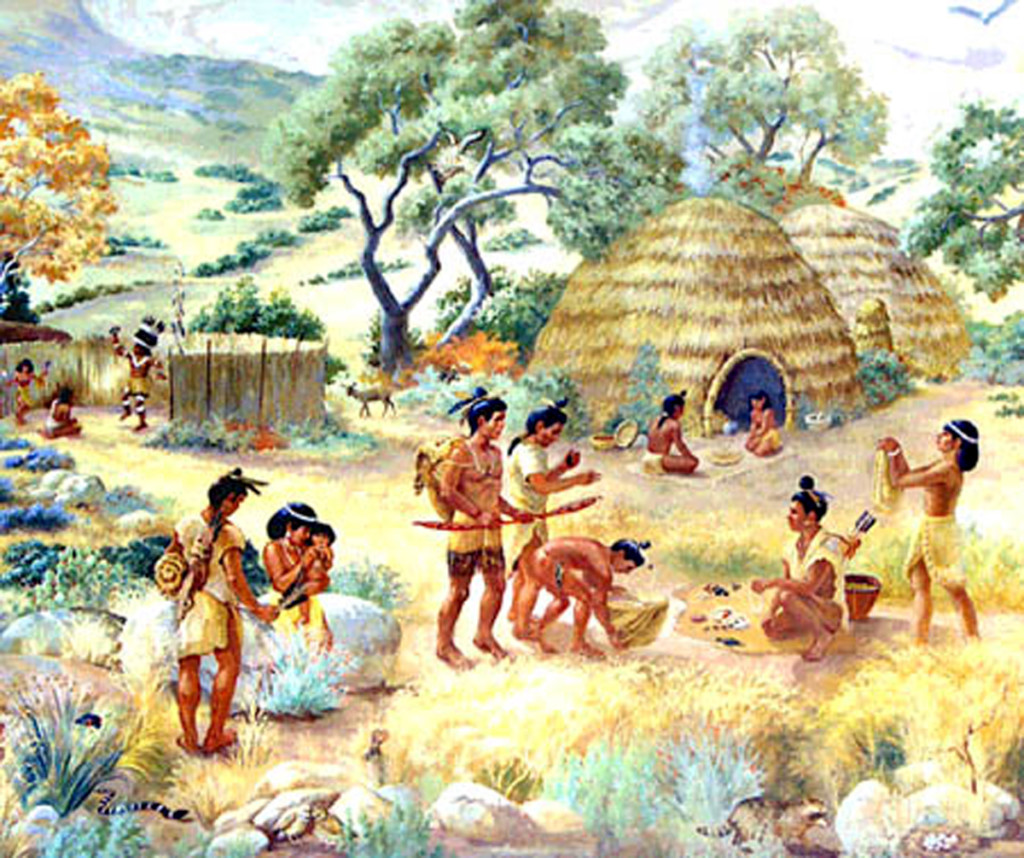

–courtesy Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History–

In Goleta neighborhoods there are more noticeable signs…. And a bike path named in her honor as well! You may have heard that creek name before, but who was Maria Ygnacio, and why would she have a creek named after her?

And a bike path named in her honor as well! You may have heard that creek name before, but who was Maria Ygnacio, and why would she have a creek named after her?

–courtesy Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History–

Well, first off, the signs have her name wrong. Her real name was Maria Ygnacia, spelled with an A, and she was a Barbareno Chumash woman raised in the Santa Barbara/Goleta area. While you won’t read about her in Goleta, The Good Land or older history books written by European settlers, Maria is the only Chumash woman to leave her mark on Santa Barbara County and she is memorialized, albeit spelled wrong, on many signs and maps today.

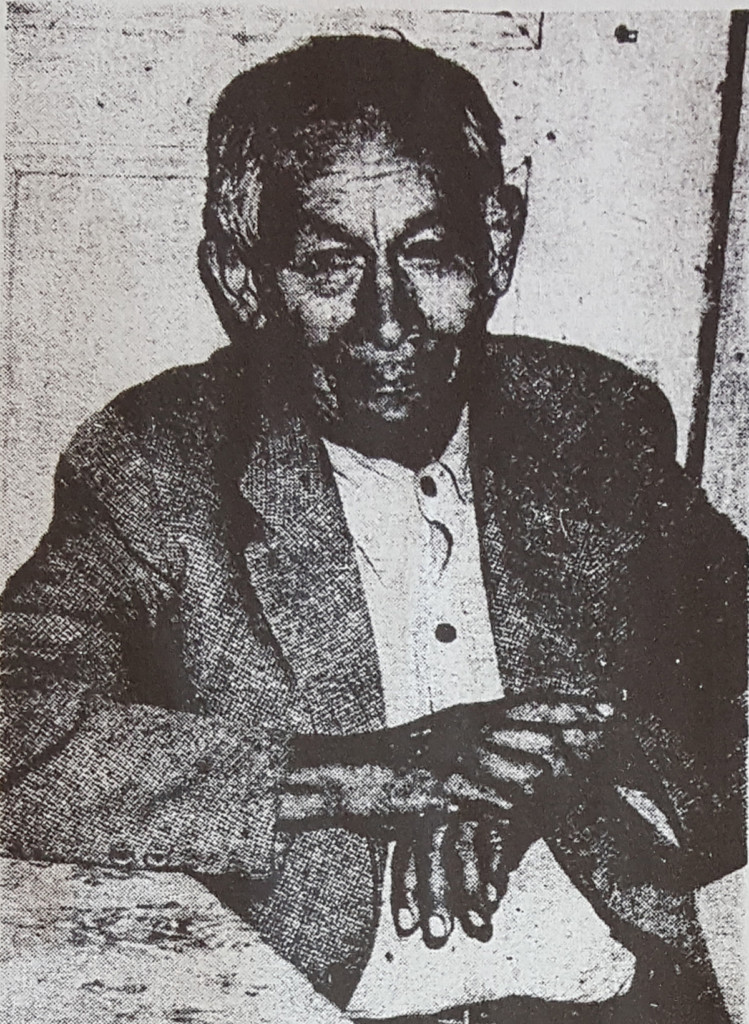

Much of what we know about her has been passed down to her descendants in stories told by her son’s wife and recorded by this gentleman, John P. Harrington. He was an extraordinary figure in the world of American Indian studies, and most of what little we know about the Chumash language is due to his efforts. The written records of the Santa Barbara Mission also tell part of her story, because the Mission played an important part in her family’s lives.

Maria’s story begins in 1769, the year her mother was born. The same year the Portola expedition made its way overland from Baja California, passing through Santa Barbara.

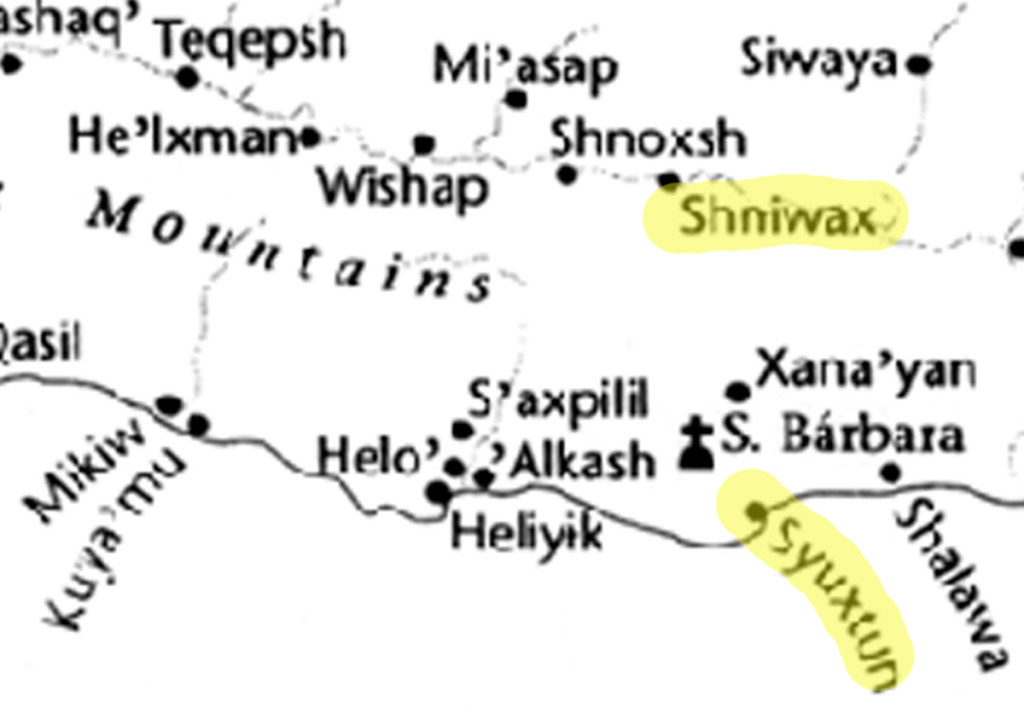

Her mother married Pablo Lihuisanaitset, who was from a powerful family in their society. They lived over the mountains in the village of Shniwax, along the Santa Ynez River.

Some years later, Pablo assumed the inheritance of his mother’s lineage, and he and his wife moved to the coastal town of Syuxtun so he could take his position as a wot, a chief. The large town of Syuxtun, a political capital, was located west of the mouth of Mission Creek in present day Santa Barbara.

Maria Ygnacia was born in Syuxtun in 1798 and was baptized at the Mission on April 17, 1803. She was about 5 at that time, and by then about half of the people living at Syuxtun had been baptized. Soon after, her family moved back over the mountains to Shniwax.

Because Maria Ygnacia had been baptized, her parents would come once a year to visit the padre at the mission. There they would receive their annual allotment of a blanket and a dress. A severe drought eventually forced the remaining Chumash into the missions for survival, including Maria’s family.

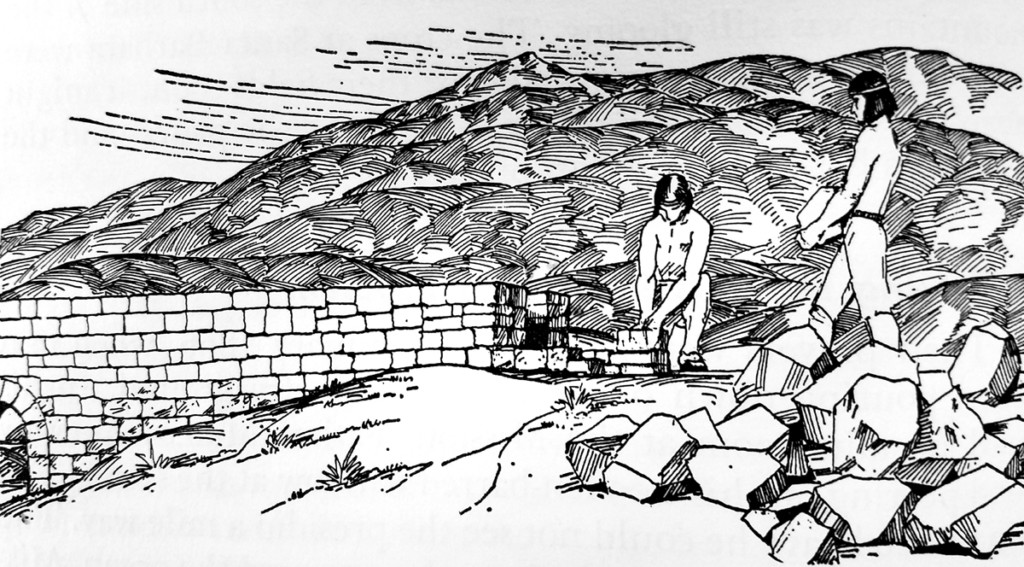

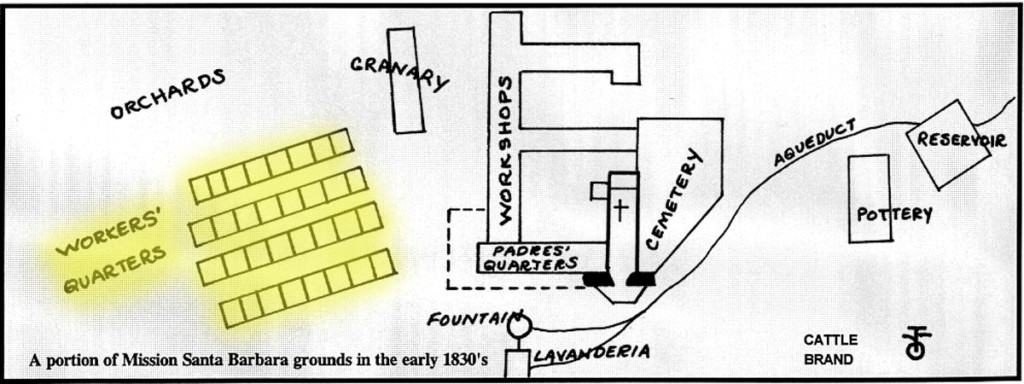

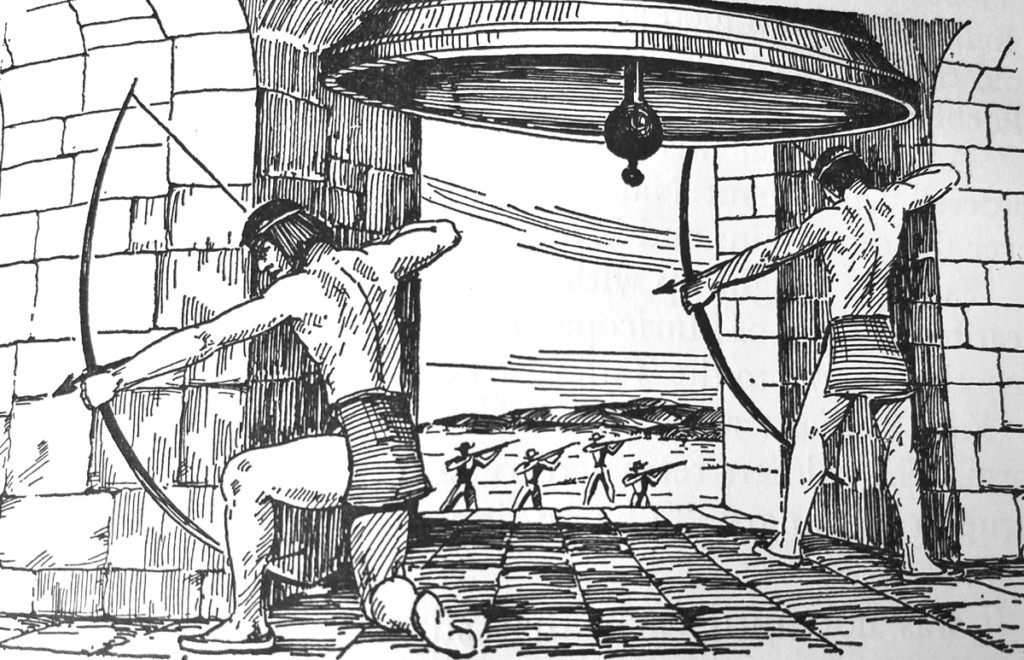

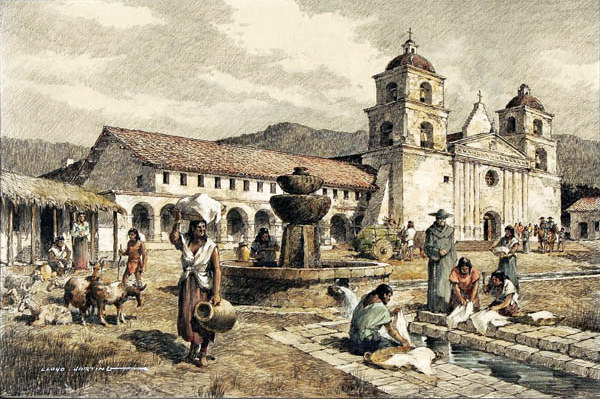

The Chumash that were living at the mission were used as labor for construction of the mission and the extensive water system.

The Chumash that were living at the mission were used as labor for construction of the mission and the extensive water system.

The “neophytes” at the mission lived in crowded compounds in rows of adobe apartments. The winter of 1806 brought an extreme measles epidemic and the Chumash had no natural resistance to this foreign disease. Living in such close proximity only accelerated the spread of the deadly disease and hundreds of Chumash died in a very short period of time. In this time of death and disease, Maria’s parents gave her a little brother, Pedro, who was born and baptized at the mission in 1808.

In 1812, when Maria Ygnacia was 14, a terrible earthquake struck the Santa Barbara area. The La Purisima Mission, shown here, was completely destroyed and the Santa Barbara Mission was seriously damaged. Powerful aftershocks continued for 3 months! The soldiers at the presidio were so disturbed by the reoccurring earthquakes that they abandoned that building and lived in hastily built thatch huts and the Chumash slept out in the open. From fresh cracks made in the mountainsides, people could see a bright glowing luminescence. Chumash elders said the quakes were caused by giant serpents moving beneath the ground. They believed the serpents were unhappy because the Chumash had given up their old religious beliefs.

In 1824, there was a revolt at the area missions against mistreatment by the soldiers and the unhealthy living conditions. The Santa Barbara Chumash fought the Spanish soldiers in Mission Canyon. Maria Ygnacia and her people escaped over the Santa Ynez Mountains back to Shniwax, along the Santa Ynez River. From there they made their way through the mountains to the Tulare swamps in the Central Valley, where the Yokuts people welcomed them. The Chumash from Santa Barbara finally agreed to return to the mission if they would not be punished.

The years passed and Maria Ygnacia and her family obtained a grant of land in a canyon near the mission vineyard.We don’t know exactly when or why Maria was given this land at a place called the Alikon, but her third husband had been a long time mission acalde, (an Indian official). Experts think the parcel was given to Maria’s husband in the late 1830’s for his long service to the mission community. When he passed away, Maria Ygnacia became the sole owner. Folks started calling the creek that flows down from the mountains and through her property, the Maria Ygnacia Creek.  Today if you drive up Old San Marcos Pass Road you can see the site of the Alikon, where Maria and her family lived and thrived for years.

Today if you drive up Old San Marcos Pass Road you can see the site of the Alikon, where Maria and her family lived and thrived for years.

Maria Ygnacia lived there with her mother, close relatives, and her two young children. Without this land grant, her family would have lost their language and they would have been split apart. The Alikon was their cultural safe haven, where they ate their own foods and they spoke their native language. For that reason, the language came down through her descendants to the present day Chumash of Santa Barbara. (The existing descendants have no fluent speakers left, but they hope to change that soon.)

For as long as anyone could remember there was an orange orchard at the Alikon and it got the nickname Indian Orchard. Stagecoach drivers used to point out the Valencia orange trees that were said to have been brought from Spain around Cape Horn in 1830.

On Sundays Maria Ygnacia and her family traveled by wagon to the small chapel built by the Indians on the reservation at Cieneguitas, near the present day Modoc Road/Hope Ranch area. Yes, there was once a reservation for the Chumash in that area, but they were slowly forced out of that as well.

–courtesy Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History–

As the daughter of the wot, Maria Ygnacia would gather her people at the beach near La Goleta for ceremonies under the full moon. There they would sing their ancient songs and make offerings to the sea. Even now, if you walk along these beaches under the light of the full moon, listen to the sound of the waves. If you listen closely enough, maybe you can hear the voices of the ancient Chumash, mourning all that has been lost.

Maria Ygnacia died in June, 1865. Of the thousands of Chumash born at Syuxtun over the centuries, she outlived them all. She was most likely buried at the cemetery by the chapel at La Cieneguita. Maria Ygnacia’s most important legacies continue in the language and the stories that she passed down to her descendants, and the Catholic faith for which her ancestors paid such a heavy price to receive.

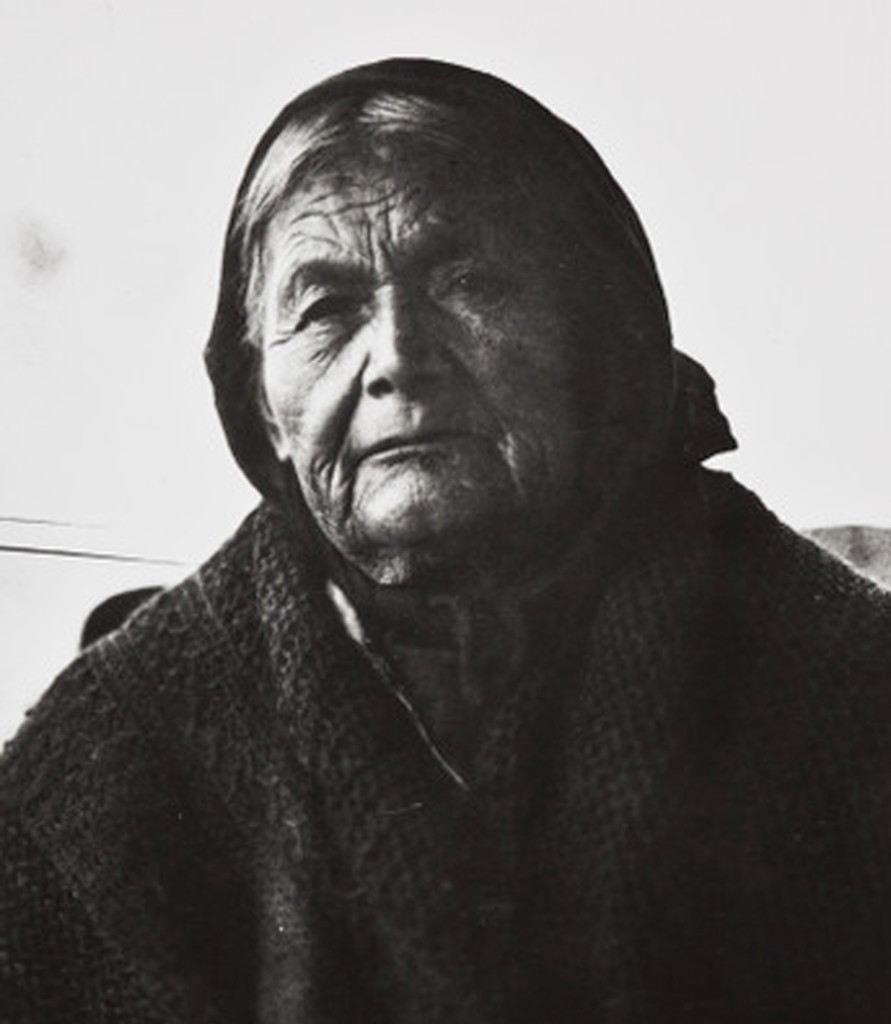

Maria’s son Jose and his wife Louisa, shown here, inherited the ranch at Alikon. At some point, Jose began going by the more masculine name Ygnacio, instead of Ygnacia. This is most likely where the confusion began with the name of the creek. Jose died in 1881, when his wagon went off a cliff, but his wife Louisa lived to be over 100 years old. Louisa worked with John Harrington to record the Chumash language and culture until her death in 1919.

Maria’s son Jose and his wife Louisa, shown here, inherited the ranch at Alikon. At some point, Jose began going by the more masculine name Ygnacio, instead of Ygnacia. This is most likely where the confusion began with the name of the creek. Jose died in 1881, when his wagon went off a cliff, but his wife Louisa lived to be over 100 years old. Louisa worked with John Harrington to record the Chumash language and culture until her death in 1919.

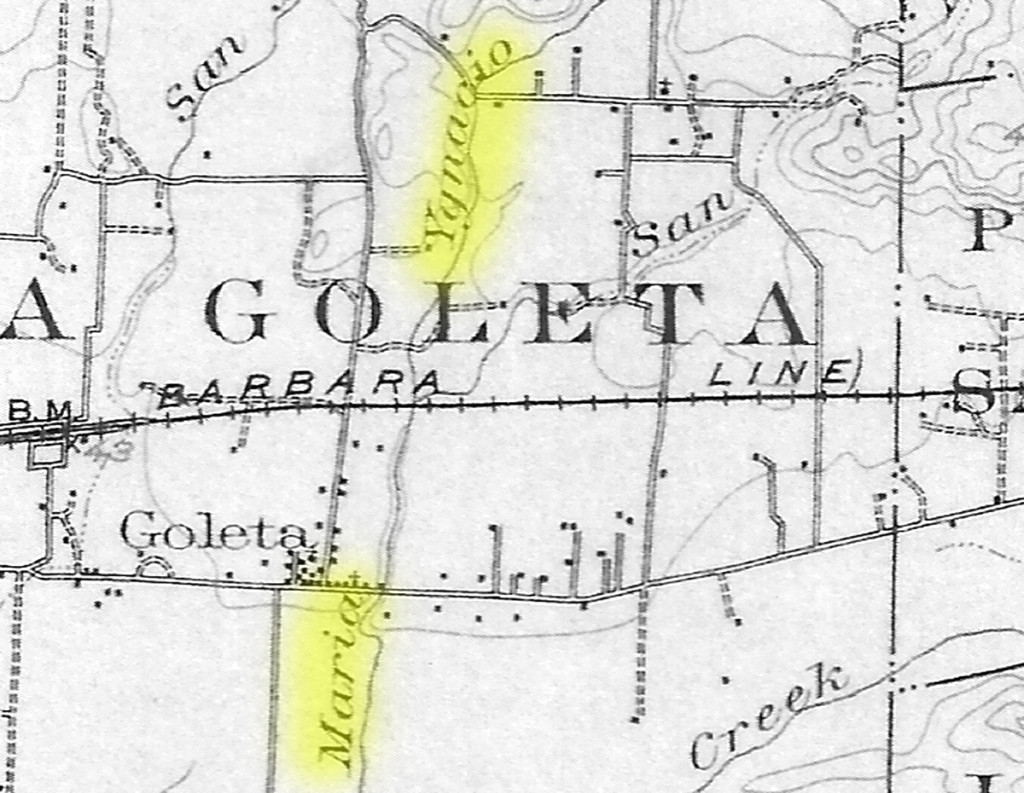

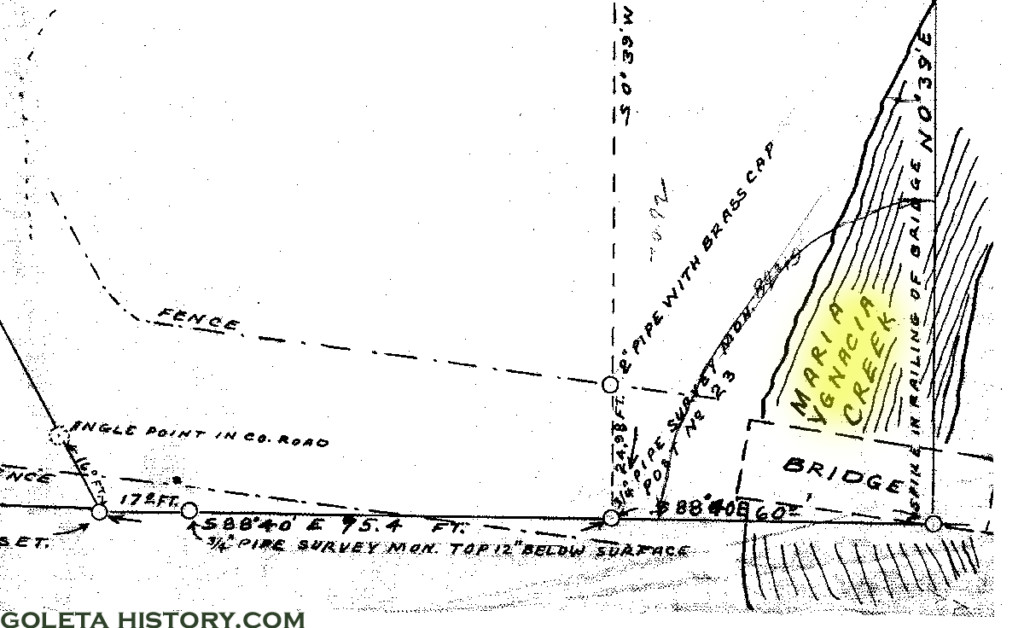

The Chumash family sold the Alikon to American settler Fred Stevens in 1907. When he bought it, there were still about 40 original orange trees, planted in the1830’s. Stevens removed all but 3 of the ancient trees, but everyone still called it the Indian Orchard. Again, probably due to her son changing his name, folks started calling it Maria Ygnacio creek, instead of Ygnacia, as seen in this map from 1903.

This map from 1909 got the name right…

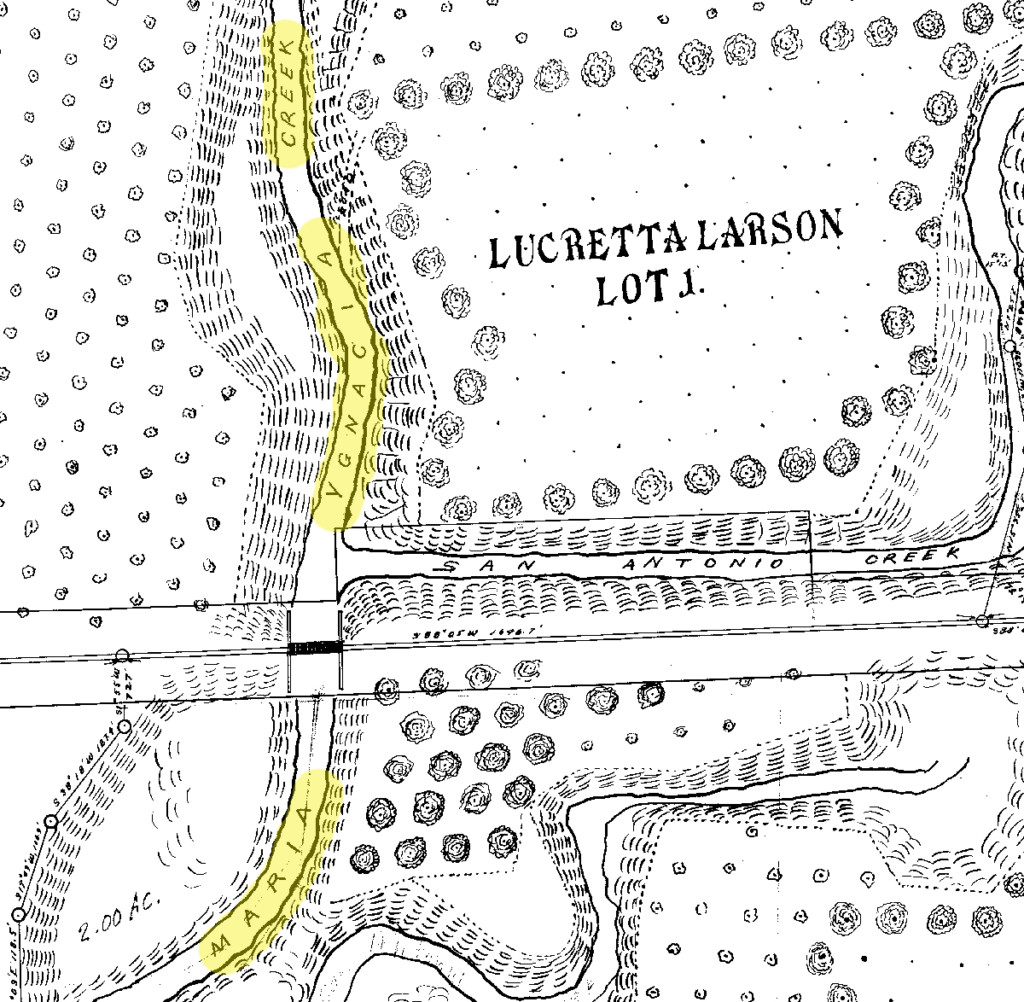

As does this map from 1922, showing the creek labeled with the correct name, Maria Ygnacia creek.

As does this map from 1922, showing the creek labeled with the correct name, Maria Ygnacia creek.

But all modern maps and government documents mistakenly call it Maria Ygnacio Creek.

In a very remote and private place, we found one sign that still has the name right…. In 1947, the News Press ran an article about Maria’s grandson, Louisa’s son, Tomas Ygnacio. He was born at the Alikon, but by then lived in a small apartment in Santa Barbara and still spoke his native tongue fluently. He told some stories that were history from a Chumash point of view, unlike any of the local history we all know now.

In 1947, the News Press ran an article about Maria’s grandson, Louisa’s son, Tomas Ygnacio. He was born at the Alikon, but by then lived in a small apartment in Santa Barbara and still spoke his native tongue fluently. He told some stories that were history from a Chumash point of view, unlike any of the local history we all know now.

Tomas remembered a story his grandmother Maria told him about when she was a young girl. One day when the Chumash laborers were laying the foundation for the mission, young Maria was playing and skipping around nearby. One of the Indian overseers told her if she had so much energy, she should stamp down the fresh laid cement! They forced her to do it and it burned her feet horribly, probably from the lime in the cement. But Tomas was proud to say that his grandmother’s footprints were in the cement at the Old Mission!

Little Maria Ygnacia was witness to a lot of amazing events in her life. The European’s diseases, a huge earthquake, an Indian revolution, the American invasion, and the complete devastation of her people.

So, next time you are heading north on Highway 101, just before you reach the Patterson Avenue exit off ramp, slow down a little and look for the small nondescript sign that reads “Maria Ygnacio Creek”. Remember her story, and remember that this land now covered with asphalt and buildings, cars and concrete, was once the home of the Chumash.

And be sure to remind people, it’s Maria Ygnacia Creek, not Ygnacio!

James Yee, the great-great-great grandson of Maria Ygnacia, contributed to this biography. He is a member of the Barbareño Band of Chumash Indians (BBCI), an organization comprised of the families in the Santa Barbara area that have proof of their Chumash ancestry. Special thanks go to Ernestine Ygnacio-Desoto, the great-great granddaughter of Maria Ygnacia, without whom this article could not have been written.

For more information about Maria Ygnacia and her descendants, watch the DVD titled, “6 Generations”, available at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. A portion of the script of that documentary film has been incorporated into this narrative.

Sources: James Yee, UC Davis, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, John Johnson, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Santa Barbara Independent, Michael Redmon, California State Library, Santa Barbara News Press

Categories: Goleta History

I heard Chumash married for life…like..Hawks, seals, and other undocumented lifestyles

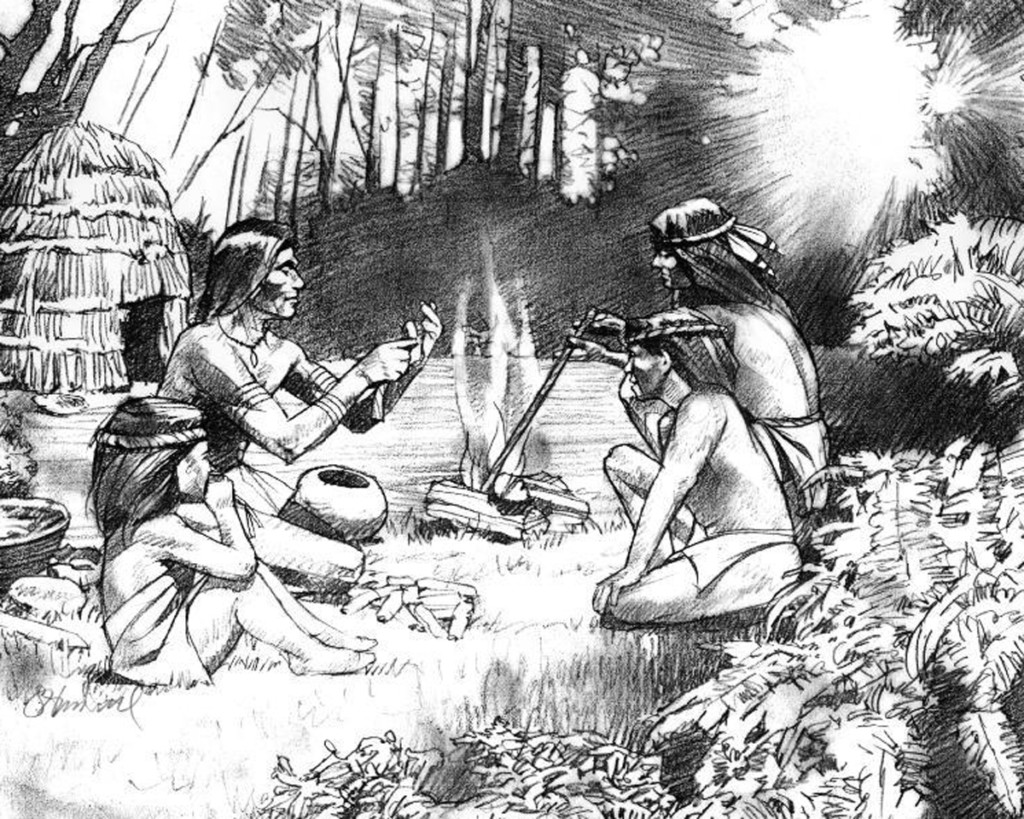

Another great article and history lesson. Is that main rendering a painting of a typical Chumash life or is it tied in to the Ygnacia family or what is imagined Maria resembled? Very curious about that painting and when it was done and

by who, part of the Harrington files?

I live on Ribera Drive, across the street from Maria Ygnacia creek. We’ve always called it “Ygnacia” in spite of the maps and signs, maybe out of some contrary streak, or maybe because of being speakers of romance languages and understanding gender agreement, something mono-lingual English speakers wouldn’t know.

It’s really cool to know more about the woman who gave her name to our creek and feel some kinship with the first people in this area.

Tom: I really appreciate this article. Was walking the Maria Ignacia path with out of town friend today and could not answer her question: ” who was Maria Ignacia?”! Great story and nice photos.

Hope you and family are well. Please give my regards to Kim and John!

Regards, Kathy Lopez

Thanks Kathy! That’s exactly why I started this site. To make our history quick and easy to access. Stay well.