There’s been a lot of talk lately about our drought and the lack of water like it’s a new thing. But a water shortage for Goleta and surrounding areas is nothing new. In fact, it’s been a problem since Europeans settled here.

Goleta enjoys a semi-arid climate that averages less than 20 inches of rain a year, but the running streams were enough to support the natives that lived here for centuries. They were hunters and gatherers that did not irrigate crops, so all they really used water for was drinking. If the creeks did dry up during a long drought, they probably packed up and relocated temporarily. While some Chumash villages grew very large, we’ve never heard of their population getting too large for their water supply, but they didn’t keep written records, so we really don’t know for sure.

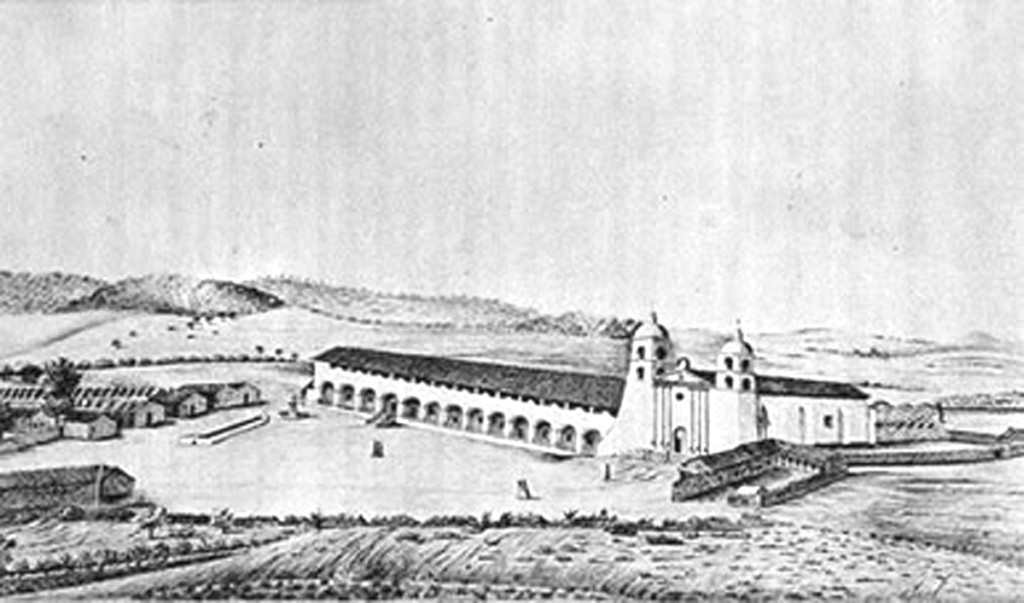

The Spanish missionaries, like all Europeans, were farmers that grew their food and kept livestock. In Santa Barbara, they soon struggled with a lack of water for their farming, their animals and for their Chumash “neophyte”population.

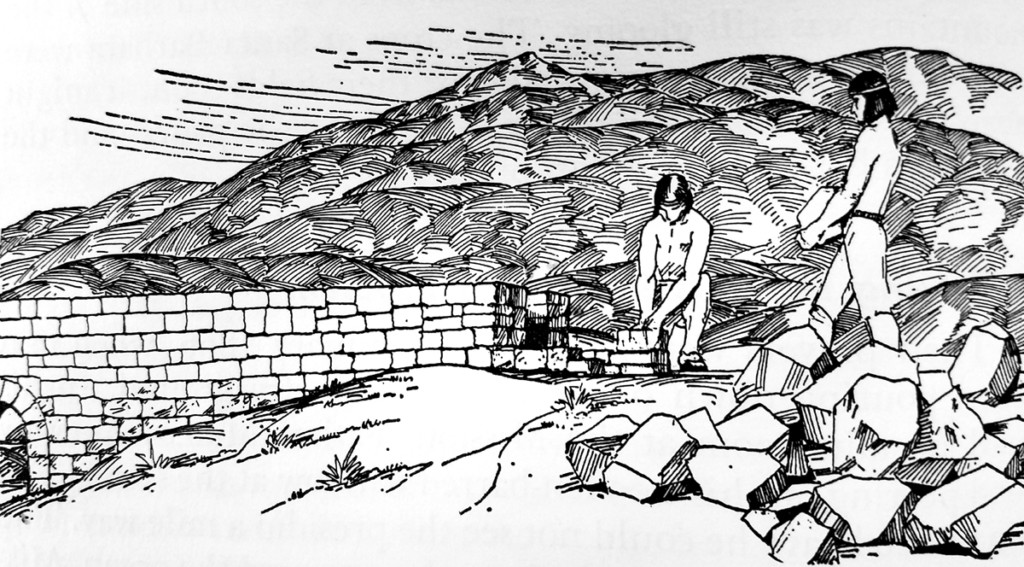

In the early 1800’s they solved their water problem with a stone dam, that can still be seen at the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, a reservoir and an aqueduct, all built by Chumash laborers.

Throughout the 1800’s, new people continued to trickle into the area, and wells were dug for water. By the end of that century the water table had dropped so low, wells couldn’t be dug deep enough to reach the water.

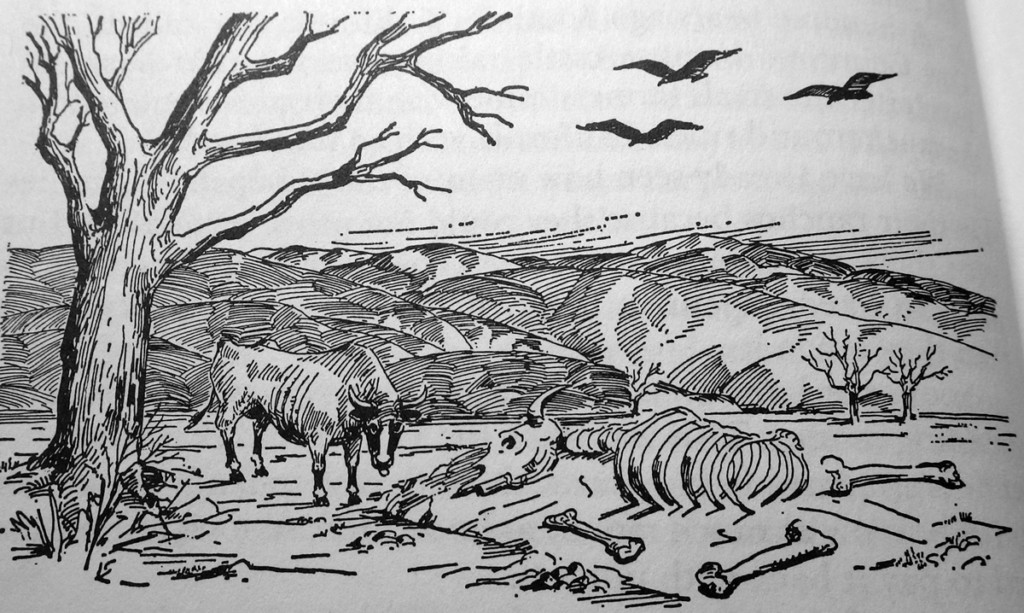

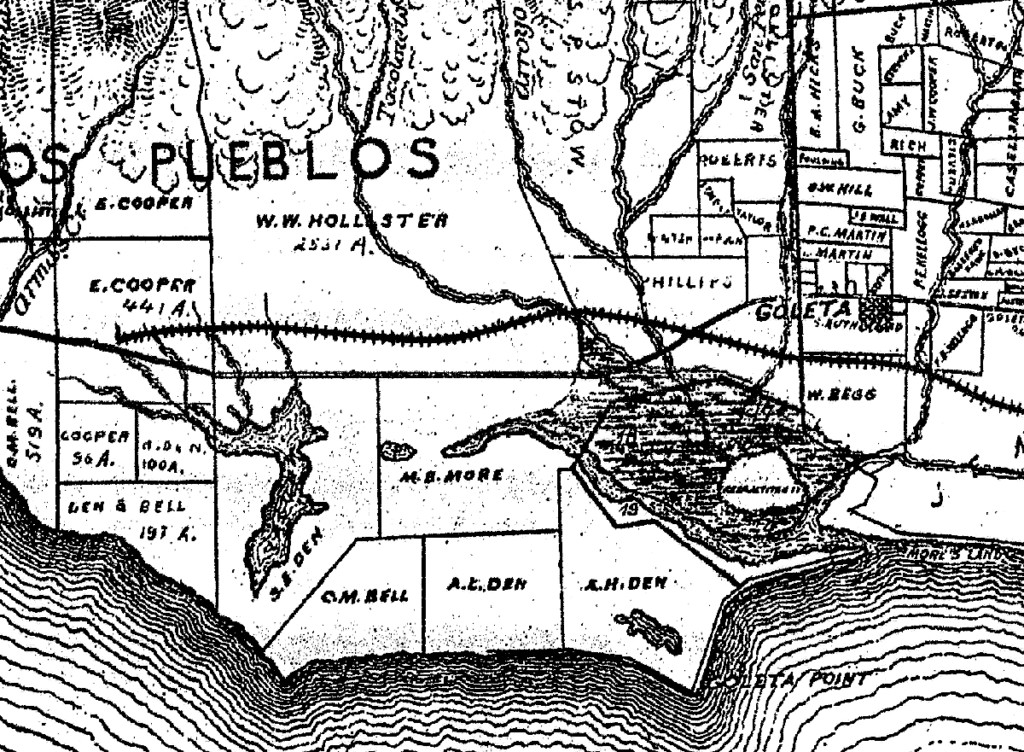

The great drought of 1864 changed Goleta forever. Spanish land grant rancheros lost their livelihood when the vast majority of their cattle died. The rancheros were forced to subdivide their massive ranches and sell smaller parcels off to survive. The result of this was more settlers coming to stay.

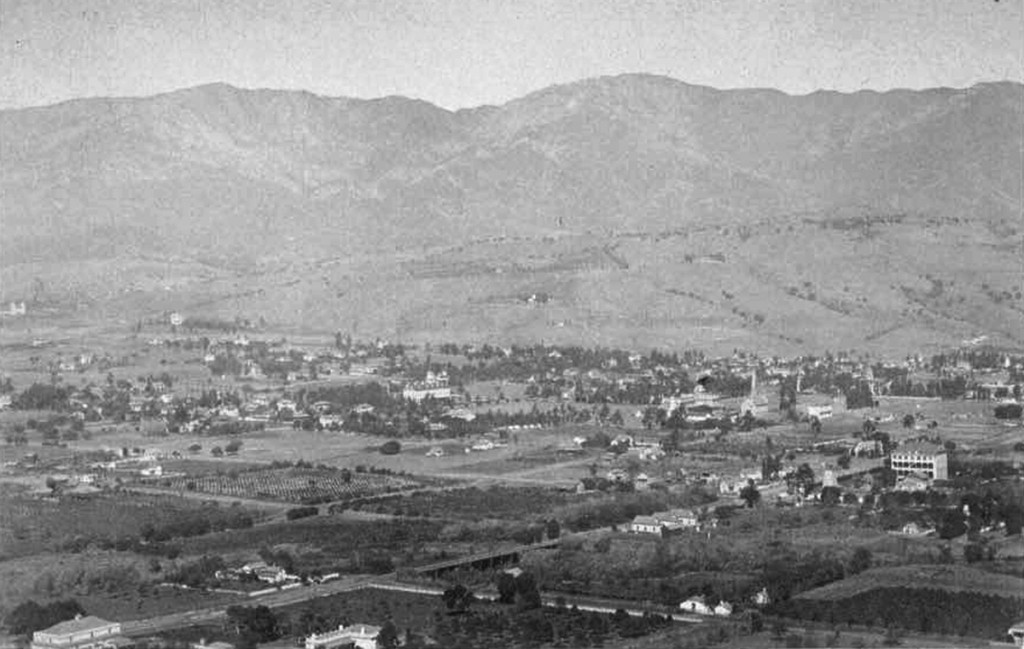

Goleta changed from a couple of huge cattle ranches to a multitude of smaller farms and ranches. The allure of the perfect climate and the rich soil of Goleta attracted farmers and horticulturalists from all around the nation. In addition to all the new people, massive orchards were planted throughout the Goleta Valley.

As Goleta Valley became an agricultural paradise, the flowing creeks could no longer provide enough water for everyone. The first well dug on the valley floor was a mere 10 feet deep, dug by Joe Sexton to irrigate this calla lily crop where Old Town Goleta is today. This well was located at the corner of today’s Cardinal and Armitos streets and it lasted for a number of years, but was continually deepened to reach the water. Soon, every farm in Goleta had its own well and, of course, the water table continued to fall as the population grew.

The first man to build an elaborate irrigation system in Goleta was W.W. Stow in 1873. An experienced politician, he used his influence to secure water rights from the headwaters of San Pedro Creek and built a small reservoir to hold it in. From there, he ran nearly a mile of pipeline down to his ranch reservoir, creating the beginnings of Lake Los Carneros. Stow spent a small fortune getting access to this water, but it paid off and his La Patera Ranch thrived.

At the start of the 20th century, the railroad was completed. Santa Barbara and Goleta became a tourist mecca, bringing more and more folks to town, and many chose to stay.

Santa Barbara dug a tunnel into the mountain wall at Cold Springs Canyon above Montecito. This tapped into the “sandstone sponge” our mountains are made of and supplied some water for a while, but that soon ran dry too.

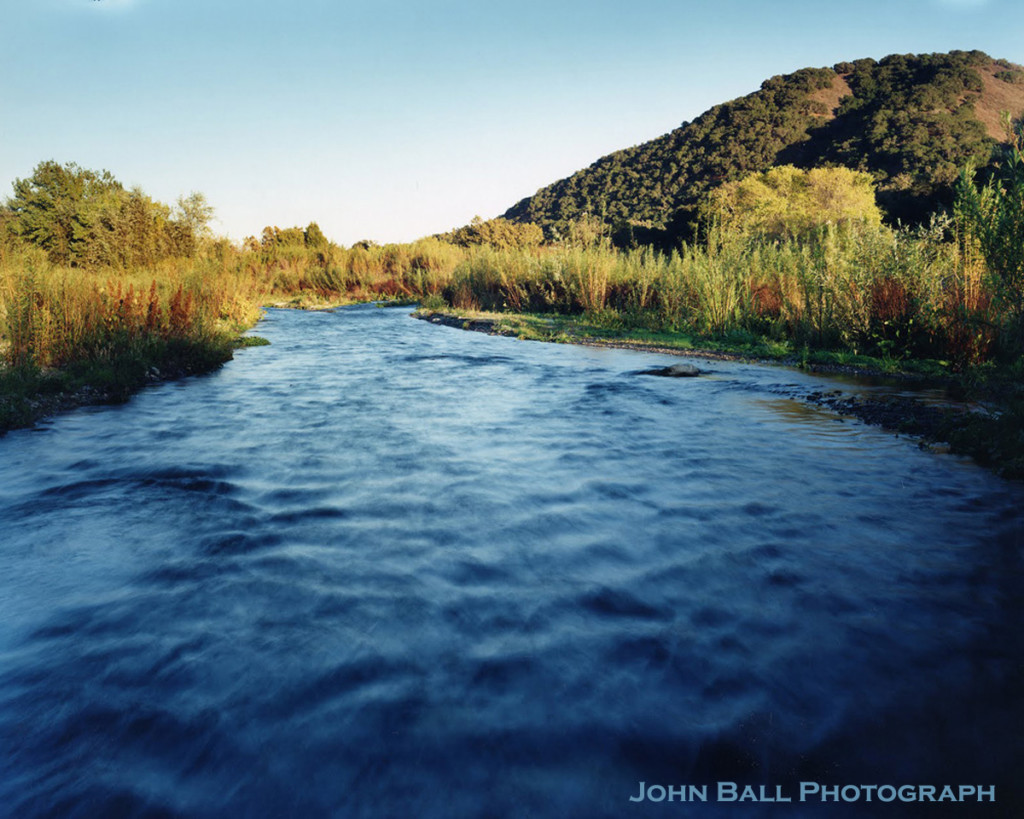

Civic leaders next looked over the mountains to see the Santa Ynez River and all that precious water flowing into the ocean. In 1912, they dug the Mission Tunnel that started at the end of Tunnel Road, went 4 miles through our mountains and tapped into the Santa Ynez River. In 1920, the Gibraltar Dam was built on the river and a few years later, Juncal Dam was built further up the river to hold water for Montecito. Lawsuits from farmers down the river followed soon thereafter, but a court ruled in favor of Santa Barbara.

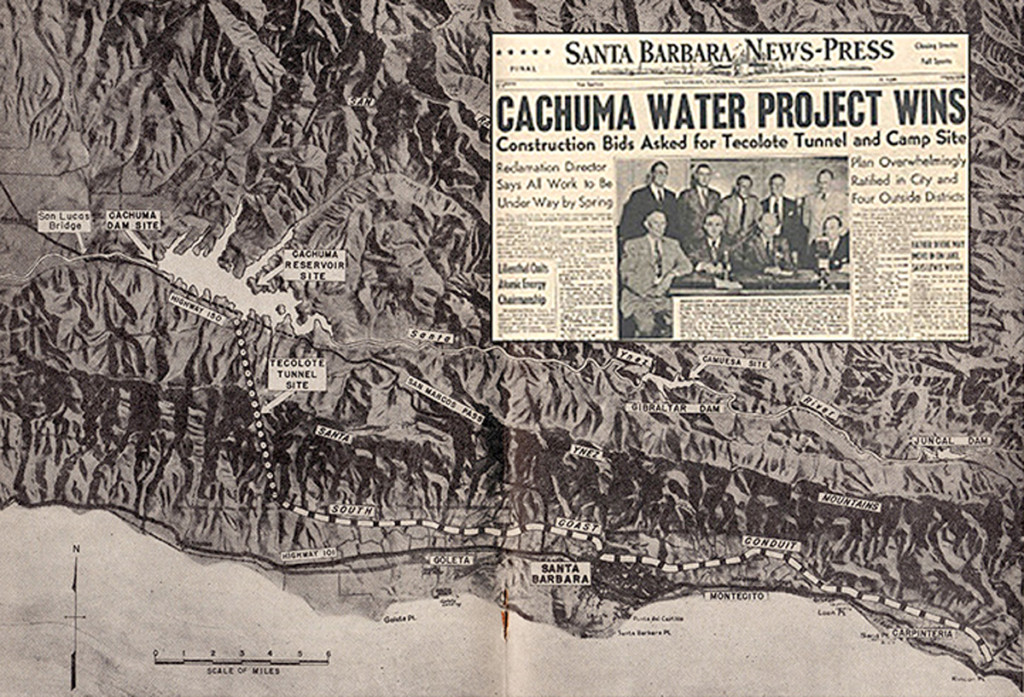

After WW II, many veterans and their families settled in the Santa Barbara /Goleta area creating yet another population boom. This created another water shortage in 1948. It got so severe, Santa Barbara passed a law forbidding lawn watering and car washing. In 1949 the Gibraltar Dam was raised another 13 feet as a temporary fix.

This time the problem was so serious, the Federal Government got involved. After a long battle with county residents against the idea, the voters approved a plan to build Cachuma Dam. They assumed this would solve their water problems for a long time, but it would take several years to construct.

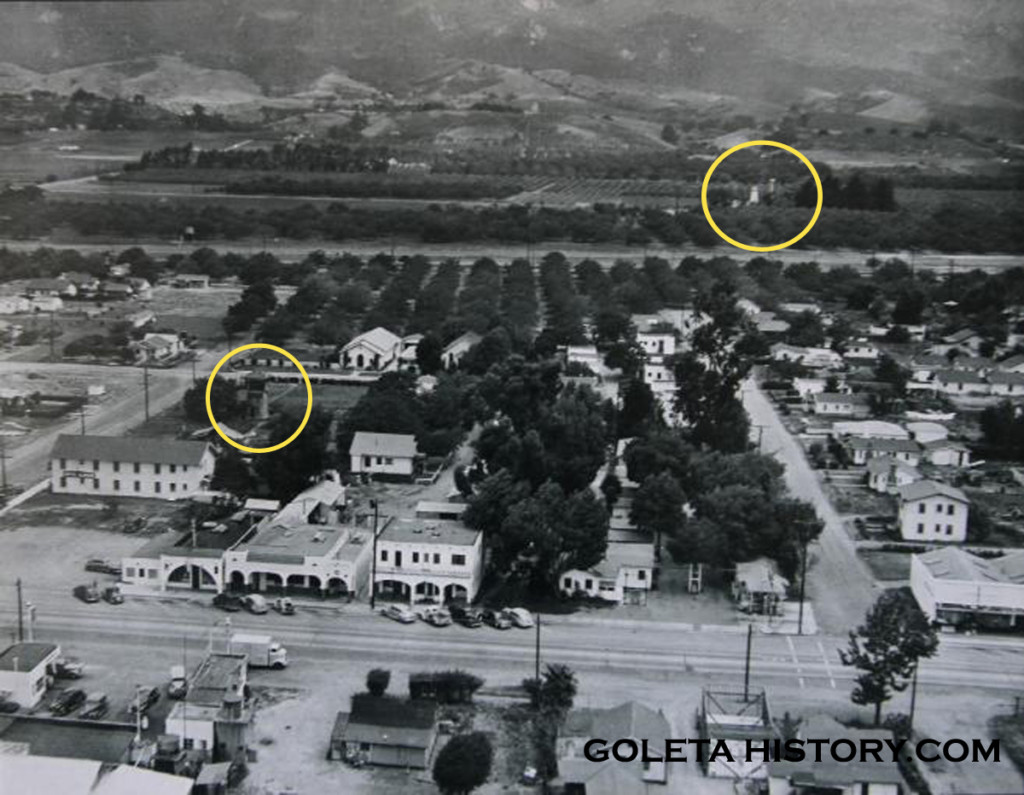

Several housing tracts had been proposed for Goleta, but a lack of water kept them from being built. Some town lots were subdivided in 1927, but construction was spotty. The water table continued to drop as the population grew. Water tanks are circled in this photo of Goleta in 1950, a few years before the Cachuma project was finished.

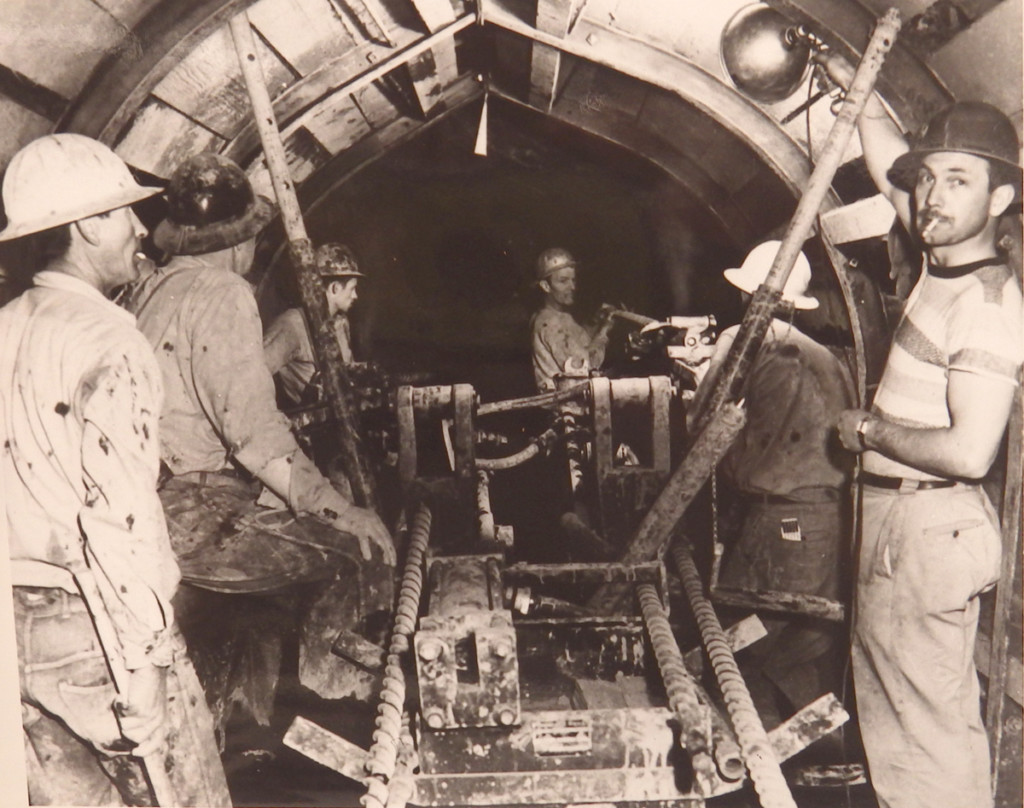

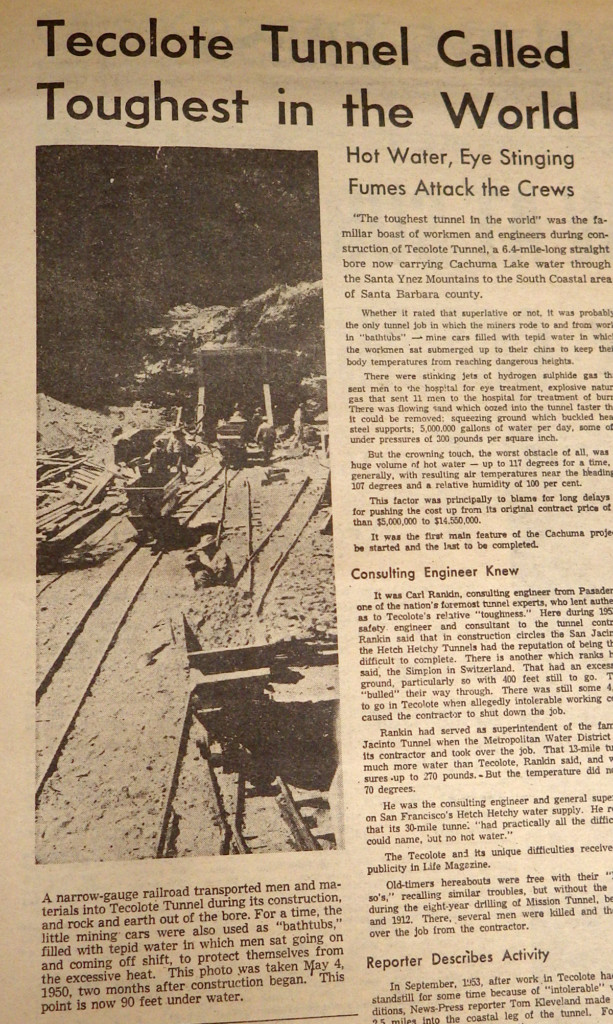

To bring the much-needed water to the South Coast, the Tecolote Tunnel was dug through the Santa Ynez Mountains, from Lake Cachuma to upper Glenn Annie Canyon.

To bring the much-needed water to the South Coast, the Tecolote Tunnel was dug through the Santa Ynez Mountains, from Lake Cachuma to upper Glenn Annie Canyon.

Over six miles long, construction was very difficult and dangerous due to the poisonous gases and steaming hot water they encountered. It was the first part of the Cachuma project to begin, and the last to finish. The Cachuma Dam was finished in 1953, but this tunnel wasn’t ready to deliver water until 1956.

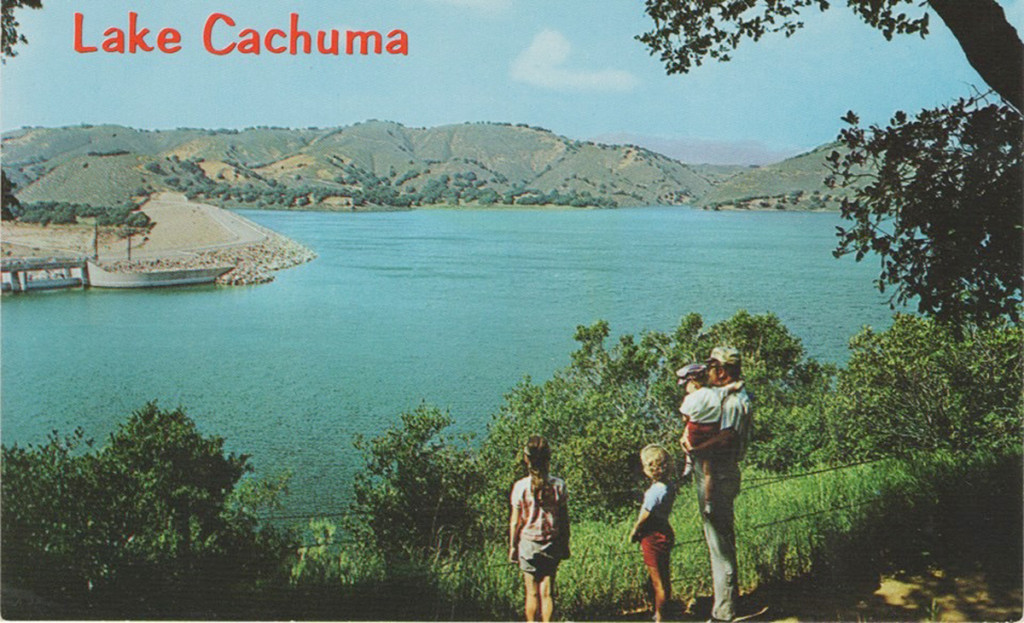

After years of planning and construction, the Cachuma project was finally finished. Even before it spilled in 1958, Lake Cachuma was a huge success and a tourist attraction to boot. While it looked like our water problems were solved, the opposite was true.

Cachuma was finished just in time for the first industrial firms to arrive alongside the new University of California Campus in Goleta. The allure of living in small town Goleta with an unlimited supply of water was strong, and the people poured in.

The same year Cachuma was finished, 1956, Goleta’s first big modern housing tract was approved. It was called Kellogg Park and it was 118 houses built between Kinman and Tecolote Avenues. This photo from the front of Goleta Union School in 1949 shows the location of the future housing tract. (Notice the For Sale sign!)

In 1956, Raytheon opened their Electromagnetic Systems Division in Goleta. It was one of the first of a new age of high-tech industries that would flourish and bring thousands of new employees to the area. By the end of the 1960s, military-industrial corporations were the main employers in the Goleta Valley.

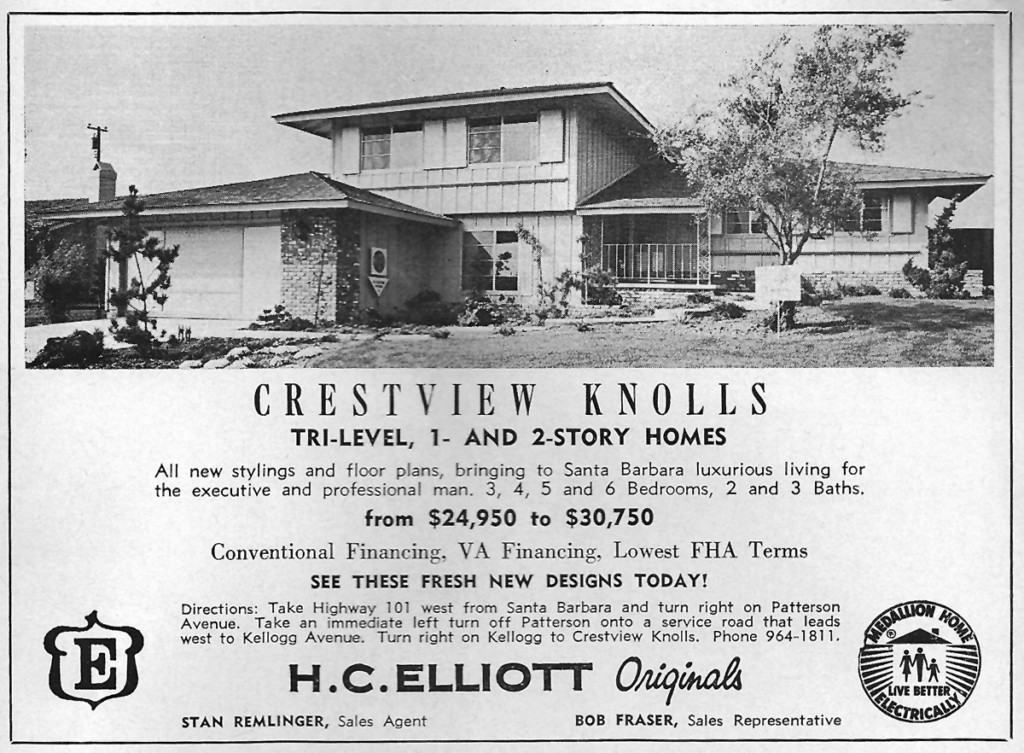

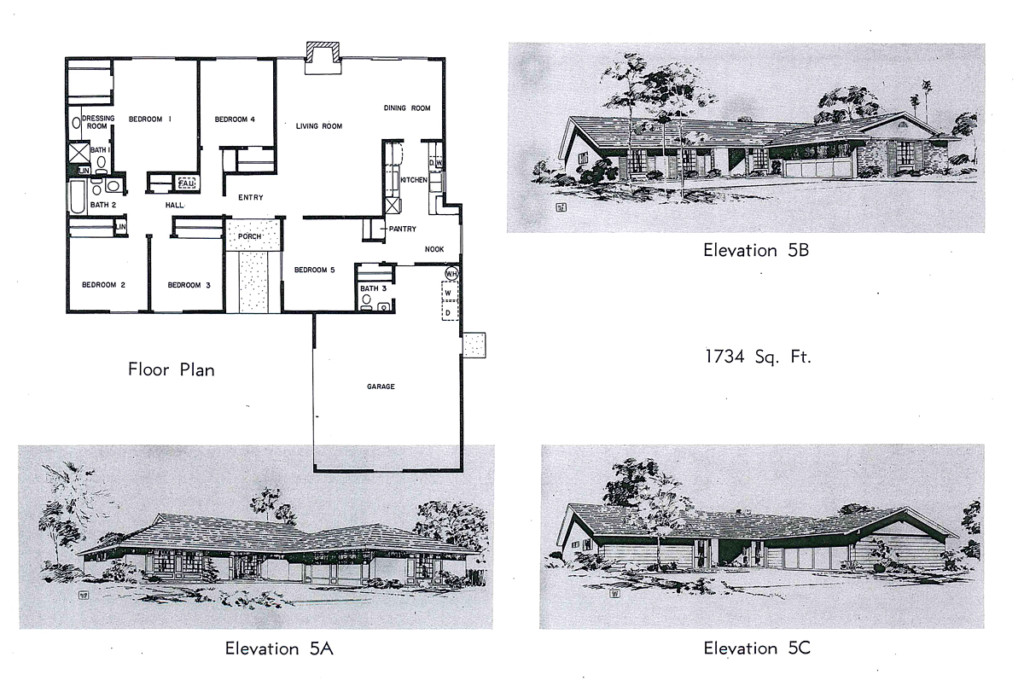

In 1959, a major subdivision of 368 houses called El Encanto Heights was built. Housing tracts began popping up everywhere, as fast as the bulldozers could mow down the orchards. By 1960, 1,000 new homes were ready or under construction and between 1960 and 1965, Goleta’s population grew 122%.

Houses spread across much of the valley as people flocked to Goleta for its climate, recreational opportunities and scenic beauty. Many of the new residents were looking to escape the traffic and smog of Los Angeles.

In 1962, Santa Barbara County authorized a General Plan for Goleta that allotted 15,000 acres for homes, 1,400 acres for open spaces and 0 acreage was listed for agriculture!

More orchards were subdivided, and the Goleta Water District converted countless agricultural water meters to residential meters, resulting in the loss of thousands of acres of agricultural land over the last 60 years.

The greater Goleta Valley population grew from 50,000 in 1970 to 73,000 in 2000. As the housing closed in on remaining farms, ranchers felt the pressure to sell. One rancher stated, “A developer from San Fernando Valley has offered me more cash for my ranch than I could hope to make in twenty years of hard work.”

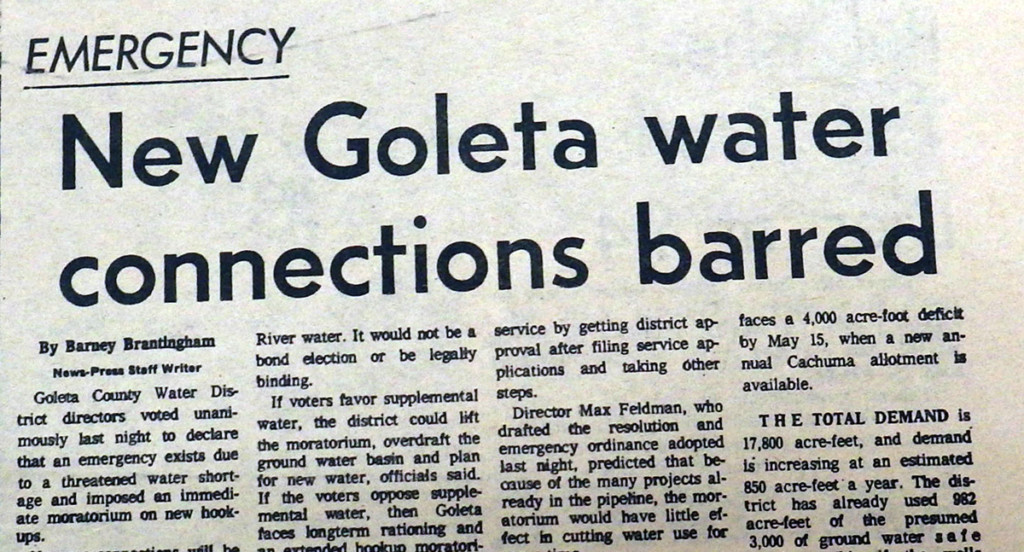

Responding to the droughts of the 1970s and early 1980s, the Goleta Water District declared an emergency and placed a moratorium on building, limiting the number of water meters issued to developers. But by 1983, the rules were changed to allow meter conversions if the housing used less water than the farm.

In the mid 1980s, the Goleta Water District introduced the first low-flow toilet rebate program in the United States, as well as the first large scale effort to replace shower heads with low-flow models. The district also began to encourage water efficient landscaping.

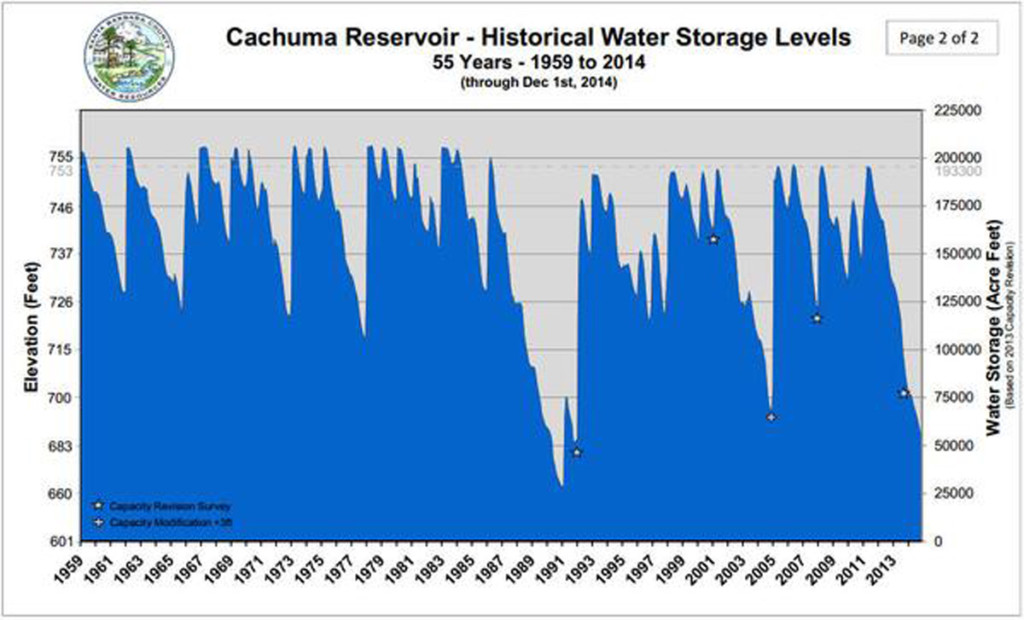

Lake Cachuma levels got so low in the early 1990s, mandatory conservation measures were imposed, water rates were raised, and groundwater pumping was stepped up. In 1991, Goleta Water District customers voted to purchase an allotment of imported water from the State Water Project. The building moratorium was lifted in 1996, but not because of State Water…..

It was due to Mother Nature. A couple of years of heavy rainfall refilled Cachuma and the reservoirs and all the talk of water conservation ceased.

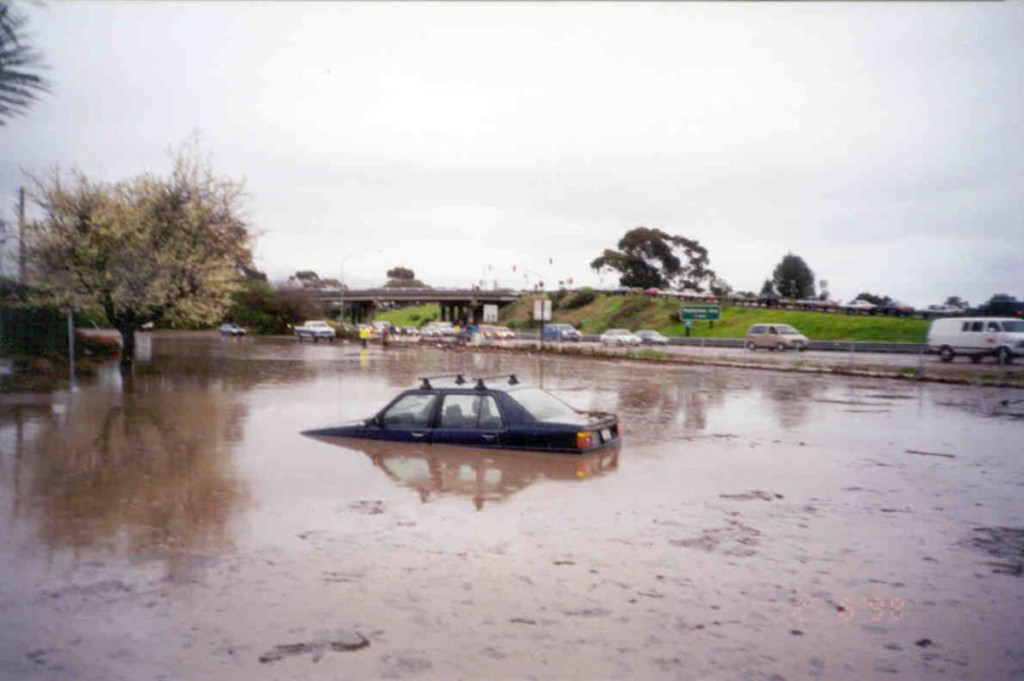

No matter what efforts man makes to beat the reoccurring droughts, the only real cure is rain, and a lot of it, which usually results in flooding. The winter of 1952 ended a drought.

There was plenty of rainfall during the growth spurt in the late 1960s.

And the drought of the early 1990s ended like this.

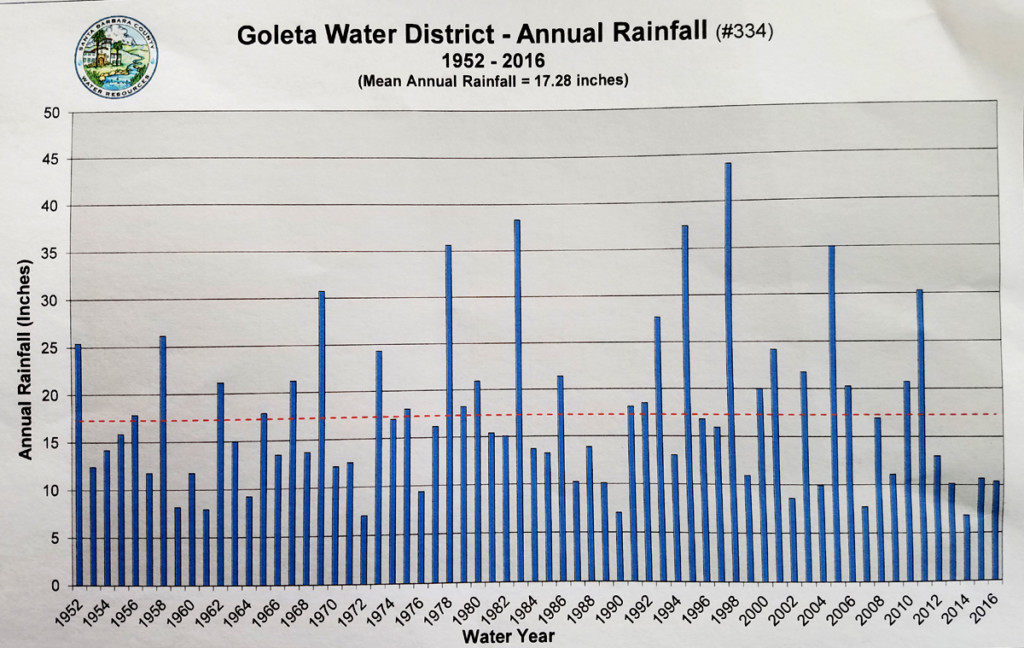

This chart sums it all up. Goleta has droughts and floods over and over again. The one most important factor that this chart doesn’t show is the steady population increase.

The same climate that offered droughts to this Goleta….

Will surely offer more frequent and more severe droughts to this Goleta.

In 2017 Goleta is once again in a severe drought, yet the growth continues. Today’s civic leaders insist we must make room for more people.

Thousands of new housing units are approved and under construction, and UCSB is growing faster than ever. So, it seems Goleta’s water problems will never be over. The more straws you stick in a glass of water, the faster it disappears. Folks can blame the climate for our water woes, but the real blame falls on us.

Today, Goleta is enjoying an above average year of rainfall, our water supplies are being replenished and the talk of the unprecedented drought will end. Until the next one….

Sources: Edhat, Santa Barbara News Press, Jack Elliot, John Ball, Adam Lewis, Goleta Valley Urban Agriculture Newsletter, Sung a lot of songs, Darwin Bondgraham, Tom Palmeri, Goleta Water District, Santa Barbara Airport,Goleta Valley Historical Society, Jeff Oien, Noozhawk

Categories: Goleta History

Rancho Embacadero uses the creek water of Tecolote Creek to fill the reservoir on Farren Road which then irrigates the avocados and lemons in their Ranch. The pipeline is a gravity feed system from the back canyon all the way to the reservoir. Build in the 1932 by Silsby Spalding

who built and lived in the Hacienda at the end of Vereda del Ciervo. Historic water rights.

Thanks Pat. Look for a page on Tecolote Canyon on this website soon…