When you’re driving out to Campus Point, you may not even notice this obscure little hill. But before World War II, this lump of dirt was a sizeable island and in ancient times it had a huge, thriving Chumash village on it.

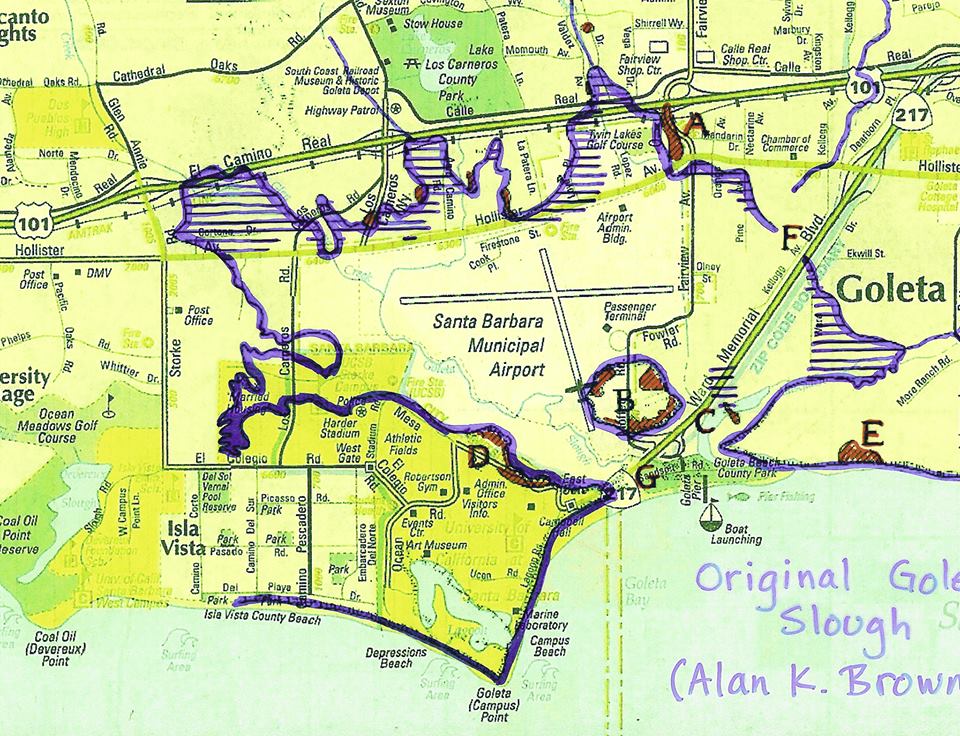

The purple line shows the area that was once the Goleta Slough and the “B” denotes the island. Stay on Fairview Avenue past the airport and you go right through the center of what was once Mescaltitlan Island.

In pre historic times, the slough was more like a bay and Mescaltitlan sat in the middle of it. With at least two fresh water springs, a thick forest, sea food and small game easily accessible and a moat for protection against neighboring enemies, this island was the perfect location for a large population to flourish, and they did.

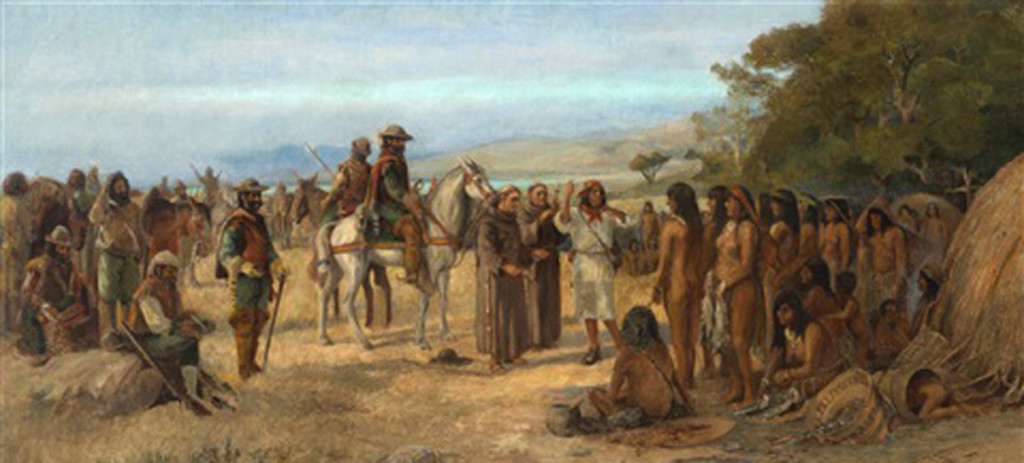

The first Europeans to discover the island were on the Cabrillo Expedition that came through in 1542. They observed the large population living on the bluffs of the bay and on the 64-acre island, then known as He’lo. At this time, it was probably the largest settlement on the California coast. Cabrillo anchored off of Dos Pueblos for one night, then he was on his way, searching for a Northwest Passage.

Shortly after Cabrillo sailed by Goleta, he died from injuries he obtained on San Miguel Island. According to Walker Tompkins, Chumash legend says that two large ships anchored in the slough and their crews buried their leader on Mescaltitlan Island. Historians debate the final resting place of Cabrillo to this day…..

After Cabrillo, several other explorers passed by, but none of them recorded any detailed descriptions until1769, when the Portola expedition came by land. They were searching locations for a new Mission in the area. Portola brought with him Catholic priests who would attempt to map and name portions of the coast. One of the priests, Juan Crespi, recorded in his journal that they came upon a large estuary that had an island in it, and “on that island, which is very green and covered with trees, we saw a large town”. He concluded this was a “very grand spot for a very large mission”.

The Spanish soldiers were impressed by this island in the middle of a bay, heavily populated by natives. It reminded them of an Aztec legend that involved a similar island in Nayarit, Mexico called Mexcaltitlan, (pictured above). The soldiers called not only the island Mescaltitlan, but the whole Goleta Valley. Many early Spanish charts label the area as Mescaltitlan.

In 1782, two Spanish ships were sent to finalize a location for a Mission in the area. Simultaneously, a land expedition led by Lt. Jose Ortega and Governor Felipe De Neve came with equipment, soldiers and livestock. One of the ship captains, named Pantoja, described a large bay surrounded by the thickest forest he had seen on this coast, and a large number of natives and canoes. While they did want to build a mission in a heavily populated area, the sheer number of natives here was somewhat intimidating.

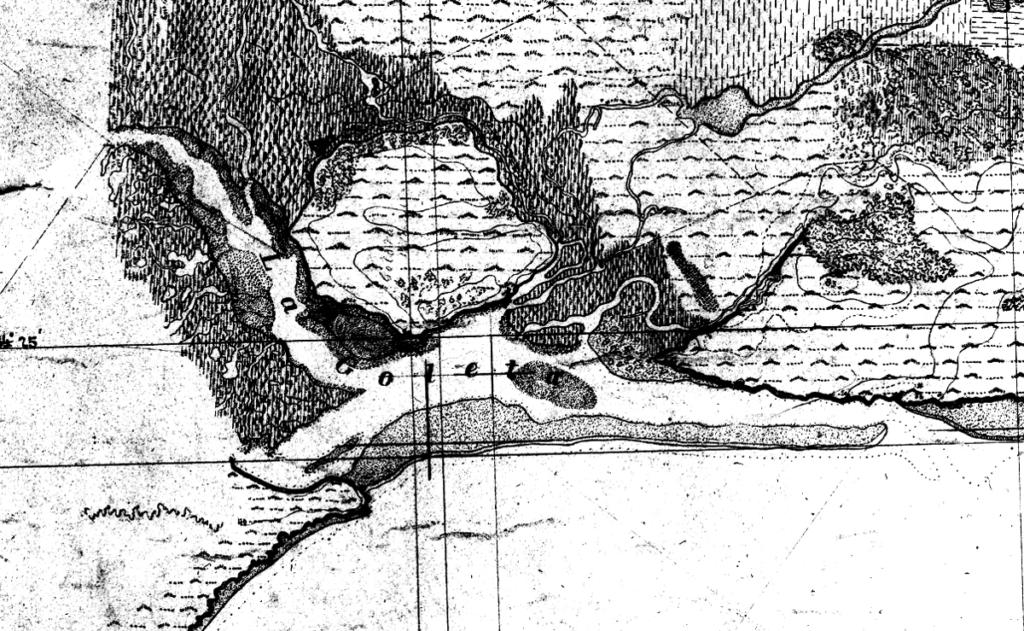

Juan Pantoja was the cartographer on this expedition and he made this detailed drawing of the Slough and the island. (Oddly, he drew two islands, perhaps an extremely high tide?) They made measurements of the depth of the slough and noted the thousands of natives living in the area. He labeled the slough, “Mescaltitan”, and he humbly named Campus Point,” Punta de Pantoja” after his favorite cartographer, himself!

The security of a moat around the island made it appealing to the Spanish military and they wanted to put the Santa Barbara presidio on Mescaltitlan Island and the mission on the More Mesa. But the Chumash in the area were constantly fighting with neighboring villages, which could prove to be a distraction from their mission. Additionally, the creeks in August were mostly dry and Goleta didn’t have a lot of rock readily available for construction purposes. For these reasons, they instead chose the spot two leagues down the coast.

On Mescaltitlan Island there were actually two large villages. The island was covered in oak trees that produced a multitude of acorns, a staple in the Chumash diet. It also had two freshwater springs and a vernal pool on it. A wide variety of seafood was readily available and the nearby canyons were full of small game. Father Crespi wrote, “On that island, which is very green and covered with trees, we saw a large town, in which were counted more than a hundred houses”.

Over time, the Chumash inhabitants of Mescaltitlan slowly left to become neophytes at the mission or escaped into the back country, where they eventually died of the white man’s diseases. Once the villages were gone, the trees on the island were cut down for firewood and other uses and the cleared land was used as a wheat field for the Spanish ranchos.

A series of events in the next century brought some major changes to the slough. The over grazing of cattle on the surrounding foothills was followed by large grass fires, then heavy rains pummeled Goleta in 1861 and 1862, which naturally caused flooding.

The abundance of rain caused rapid erosion and sediment poured through the creeks, emptying into the slough. Within a few years, most of the bay that surrounded Mescaltitlan Island became a silt filled salt marsh.

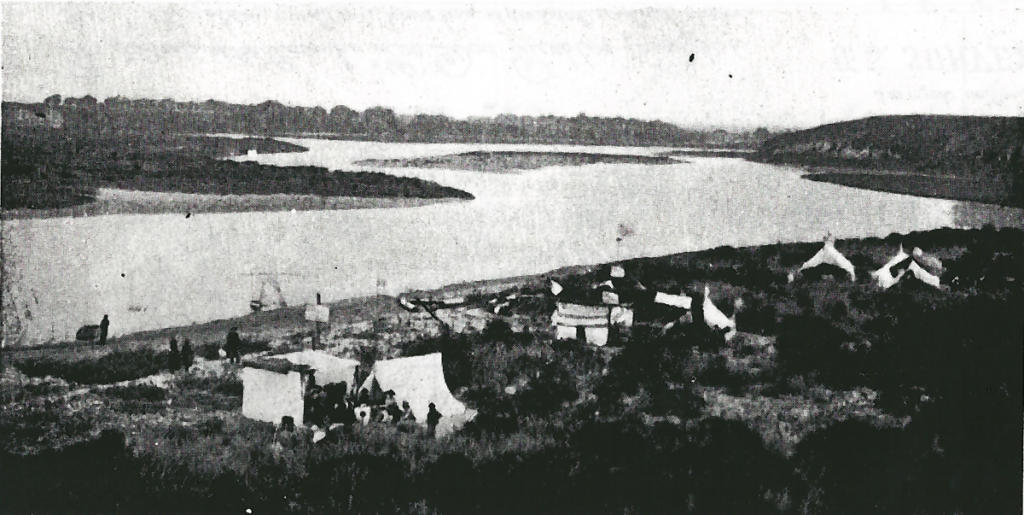

In 1876, John More bought the island and surrounding areas, seen on the right above, and used it for a bean field. He later built a house on the island for his sister, Martha Rowe. Around the turn of the century, spending summer vacations on the Goleta Slough was quite popular, as seen in this photo.

This is the first known aerial view of the island, taken in 1928. Most of the forest on the island had been chopped down for firewood by then. It appears to still be surrounded by water, but the depth was probably quite shallow.

For years, Goleta folk had dug around on Mescaltitlan for “Indian curios”. For years, many locals actually thought it was called “Skeleton Island”, a slurring of the Spanish name, but also indicative of the years of grave looting that had occurred there. Archeologists finally realized what a treasure trove the island was by the late 1920’s. Many relics were recovered and a lot was learned about the native societies that lived there.

In this photo from 1938 the slough surrounding Mescaltitlan appears to be more silt than water.

In 1941, the U.S. Government started a program to construct 250 airports across the country and Thomas M. Storke secured Santa Barbara’s enrollment in the program. Mescaltitlan Island was used as fill dirt to transform the slough into more runways.

Not surprisingly, construction crews unearthed a large amount of Chumash remains. In 1943, Phil Orr of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History found an unusual burial of a woman on the island. She was buried flexed on a large whalebone, heavily decorated with beads and abalone pressed into tar. She was thought to be a person of great importance. Unfortunately, many other valuable artifacts were undoubtedly destroyed in the rush to complete the airport.

Not surprisingly, construction crews unearthed a large amount of Chumash remains. In 1943, Phil Orr of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History found an unusual burial of a woman on the island. She was buried flexed on a large whalebone, heavily decorated with beads and abalone pressed into tar. She was thought to be a person of great importance. Unfortunately, many other valuable artifacts were undoubtedly destroyed in the rush to complete the airport.

Moffett Place is at the bottom of these photos looking east from 1943, showing a large portion of the island still in existence.

In 1944, a good chunk of Mescaltitlan Island still existed, shown under the arrow. Unfortunately, more of the island was removed for construction of the Ward Memorial Highway in the late 1950’s.

In 1944, a good chunk of Mescaltitlan Island still existed, shown under the arrow. Unfortunately, more of the island was removed for construction of the Ward Memorial Highway in the late 1950’s.

That left only this small chunk of the original island.

Today what’s left of the island is owned by Southern California Gas Company and the Goleta Sanitary District. So, the next time you drive past this little mound of dirt, take a longer look and try to imagine how this island looked back in the day, covered with trees and home to a large Chumash population. Mescaltitlan was a little island that played a large role in Goleta history.

A mural by local artist Larry Maser, depicting a California Condor soaring over Mescaltitlan Island, can be seen at Santa Cruz Market at 5757 Hollister Avenue in Old Town Goleta.

Sources:

Justin Ruhge, Walker A. Tompkins, Urban Hikers, Rob Evans, Ruusell Ruiz,

Santa Barbara Airport, Culture trip.com

Categories: Goleta History

Dear Tom,

Your history of Mescaltitlan Island was a wonderful and informative read. I’ve always been drawn to it since moving here in 1989. The storyboards at the little parking lot across the road from there has a nice concise history as well. I live in the mobile home park that’s located in what was the old slough. Rancho Goleta – I understand Fess Parker developed this and opened it in 1973. Wondering if you could fill in some of that history. How did Fess come to own it? How long a process did he have to go through to get the project approved? Looks like the property might have been farm land – who owned it? THX!

amazing! love the local history

Please add me to your mailing list

Done! Thanks John.

Via Mescaltilian shirts next? I am using mezcal against the virus.

At the entrance of the slough at the south of Goleta Beach Park used to be a great little surf spot in the 60’s where the sand would build up

This is an amazing story of a very sacred and historical place. It is heartbreaking to realize it was once the home of thousands of Chumash people and now it is a ravaged landscape, completely destroyed by unthinking developers. Santa Barbara and Goleta should try to refurbish the slough by relocating the airport, the gas company, and the sanitary district. These kinds of city infrastructure should never be allowed on native Indian village sites. Mescaltitlan and the estuary surrounding it could be restored and provide a learning environment, open space, and rewilded area as a trophy project for California’s finest historical indigenous landmark!

This is a very interesting article, I graduated UCSB in 1972, and lived off campus so I made a lot of trips back and forth on Ward Memorial. My wife has a connection in that her grandfather owned a slaughterhouse on what is now the airport to supply his meat markets in Santa Barbara, as in Los Carneros Rd. When the government wanted to build the airport, they used eminent domain to seize the brick building and destroyed it – would not even let him haul off his own bricks. About the same time I transferred from SBCC to UCSB I met Tom Storke when I cleaned the attic out while he worked at his desk at the Newspress building. His right-hand man, Dick Smith, hired me. My father-in-law, Ken Channell, had a contract with the Newspress for several decades to deliver the newspapers to the homes of the delivery boys. It is indeed a small, connected world. The part about burying Cabrillo is really intriguing, I wonder if the Chumash watched and dug him up for his armor, sword, etc. Hey, white people have dug up plenty of Native Americans.

Wow, lots of great information in your note. I will send you an email. Good point about the Chumash digging up Cabrillo! thanks!

My father worked for Pacific Lighting Gas Supply, which was the company that owned the property in the 40s and 50s. My friends and I used to explore the area and would often find broken bones in ditches that had been mechanically dug. One time I found a beautiful 3” bead made of soapstone, which I still have. I used to have one of a pair of skulls from a burial which had been exposed when a road had been cut into the west side of the island. We were so careless of history back then. It is heartbreaking that we waited until the island was all but gone before we recognized its value.

Thanks, Tom.

These stories help me comment on local maritime history as a docent at the SBMM.

Steve

That is awesome Steve! Glad to be of service. Thanks for the work you do there.