If you know what you’re looking at, this boring clump of ivy holds a lot of historical importance. This is all that’s left of Goleta’s once booming asphalt industry. But let’s start at the beginning.

Tar, oil and asphalt have always been present in Goleta. The native Chumash had many uses for tar and asphalt for thousands of years, probably the most important use being to seal their impressive plank canoes. The first written histories of Goleta mention how the ocean was covered with an oily surface, giving it an iridescent hue and the air was thick with an oily smell.

T. Wallace More was the first guy in Goleta to sell the tar that seeps out of the ground for profit. In the 1850s, he began selling asphalt from his newly acquired 400 acre ranch in eastern Goleta that we call More Mesa today. He found a big demand for the natural tar in San Francisco.

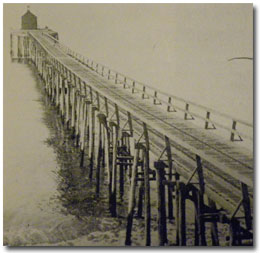

In the summer of 1874, T. Wallace More completed the construction of a 900 foot wharf on his ranch, just east of the mouth of the Goleta slough. By 1890, More had shipped over 32,000 tons of asphalt from the pier. More was getting between $12 to $20 per ton for the raw material that was used for roofing and street paving in the big city. Asphalt was the most profitable source of income for the More Ranch.

More used dynamite to blast the asphalt from the cliff, then crews would gather it up and load it into carts pulled by oxen up the ramps to his new wharf to be shipped out.

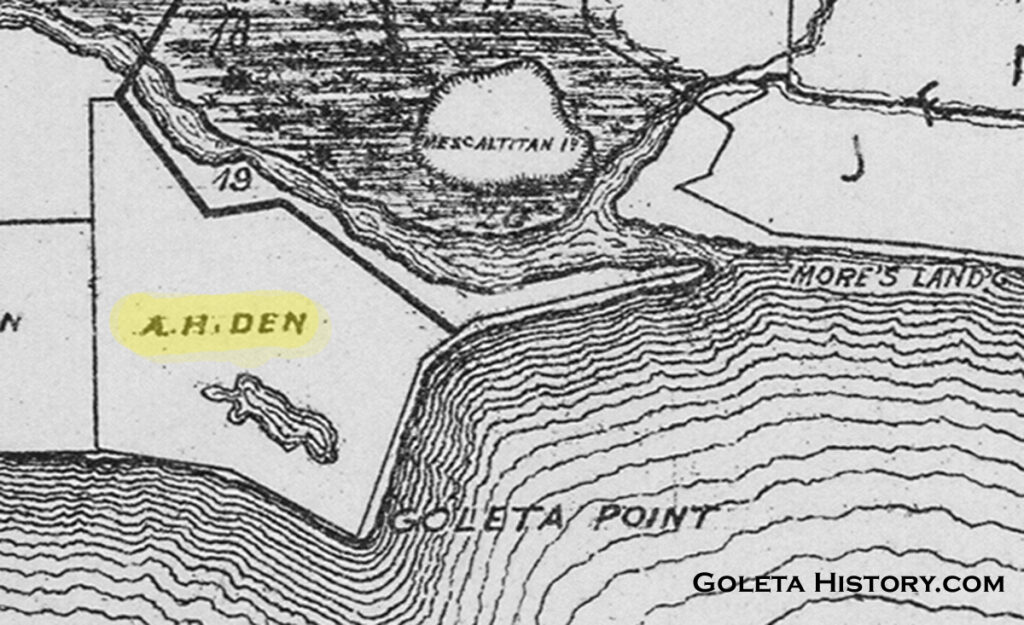

Meanwhile, on the other side of the slough there was another tar pit on a piece of land owned by Augustus “Gus” Den. Gus had suffered brain damage at birth, putting him at a disadvantage for much of his life, but his fortune was about to change. This parcel he inherited from his father, Nicolas, was covered with a thick oak grove and had no fresh water, making it worthless for farming or grazing. But it had a tar pit on it and in 1890, the Alcatraz Asphalt Company leased the property from Gus.

Alcatraz had another asphalt operation in Carpinteria, but like the More Ranch tar pit, they only did surface mining. Digging or blasting the asphalt up and then gathering it off the ground. On the Den property they would build the only local asphalt mine to use deep shafts, eventually going down to 550 feet, and it was very lucrative for both the Alcatraz company and Gus Den.

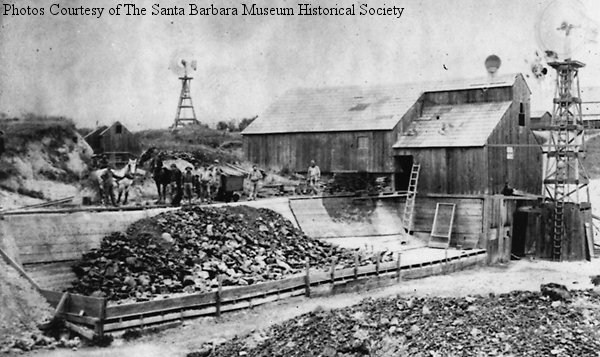

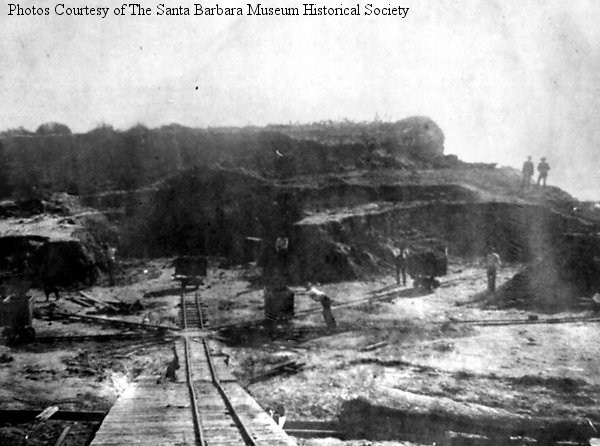

Hard to believe this industrial looking scene was right next to the scenic lagoon on the campus of UCSB! Alcatraz operated this mine from 1890 to 1898. When the Goleta plant was operating in its heyday, it pumped out 60 tons of asphaltum every twenty four hours. Chunks of solidified tar were loaded onto horse drawn wagons, each wagon carrying four tons, three times a day, seven days a week, down to the train station at Hollister and La Patera. Once on the Southern Pacific line, the Goleta asphalt was distributed all around the country. Some of the historic streets of New Orleans are paved with tar from the asphalt mine in Goleta, California.

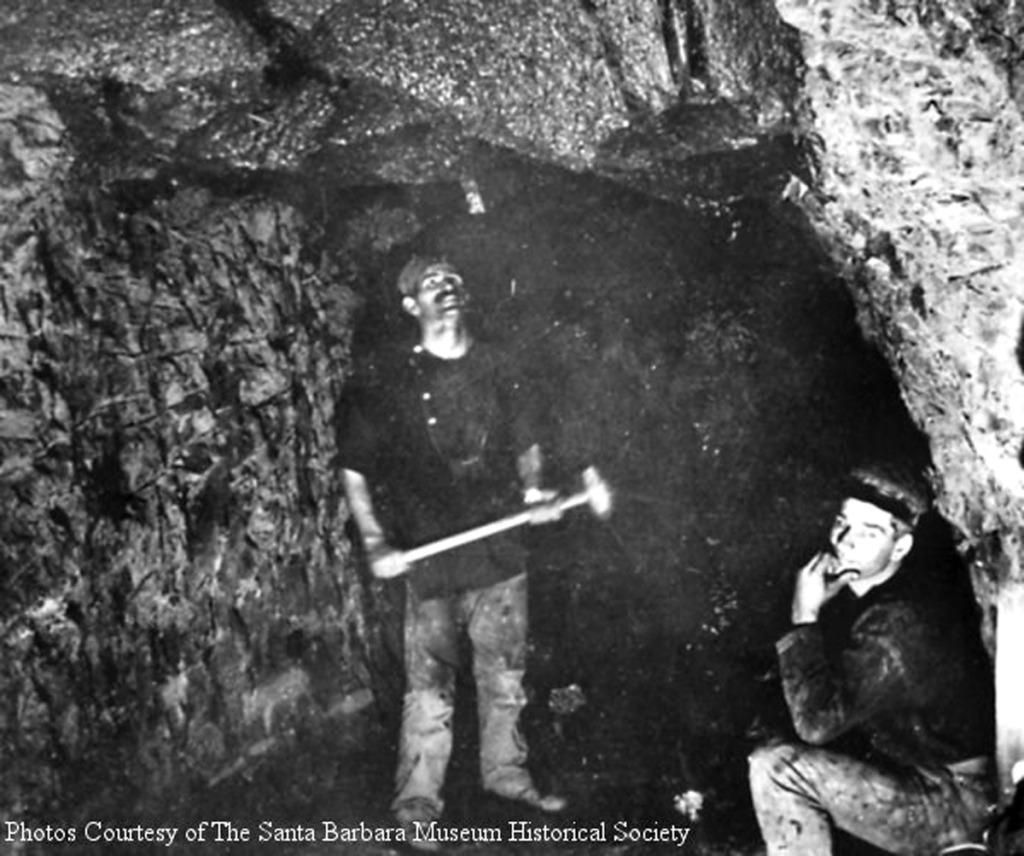

The mine employed 50 men, from local boys to experienced former gold miners, local farm workers to transients. The days were long, and the work was hard, but the pay was good. Workers made as much as $2.50 for a 10 hour shift….. 25 cents an hour! Sounds pathetic today, but that was twice as much as a farmhand made. The work was dangerous and unhealthy. Dynamite was often used to break through sections of congealed tar in the shaft, making the job even more hazardous. Two miners were killed in an underground explosion, and the air in the shafts was so polluted even the slightest open wound could bring on serious infections. Workers described the job as, “Hot, dirty, cramped and dangerous” and men often passed out from breathing toxic fumes.

The first shaft was dug 200 feet deep, right in the middle of an outcrop of asphaltum, and the nearby lagoon served as a convenient dumping place for the mine tailings. They soon realized their mistake in digging straight in, as the deeper they dug the more fluid the asphalt got, similar to digging into wet sand. So they dug another vertical shaft into solid earth, 100 feet away from the first, then every 50 feet down, they dug horizontal tunnels to tap into the original shaft. The tunnels were lined with 10×10 fir timbers shipped in from Oregon, but even these heavy supports often snapped like toothpicks under the pressure.

The dangerous work going on underground didn’t keep these Goleta beauties from hamming it up on the mine property. Left to right- Rose Sexton, Lulu Maulsby, Callie Chambers and Edna Sexton Beatty.

Shown here is the Carpinteria asphalt mine, also operated by Alcatraz. In 1898, Alcatraz closed the Goleta plant, and moved to a more economical surface tar pit on the Sisquoc Ranch.

This 1928 aerial shot of today’s UCSB lagoon shows what we believe to be remnants of the excess asphalt tailings that were dumped into the lagoon.

Today, an opening to one of the mine shafts sits beneath this clump of ivy on the busy UCSB campus. Thousands of tons of fine quality asphalt remain 200 feet below this spot, as well as the remnants of shafts and tunnels. The only existing memory of the Goleta asphalt industry and the brave men that risked their lives trying to make a living, over a hundred years ago.

Sources:

Justin Ruhge, Walker A. Tompkins, Santa Barbara Independent, Geocaching.com, Santa Barbara Museum Historical Society, Daily Nexus, Edson Smith Collection, Robin Evans, Brad Bayley

Categories: Goleta History

Hi, just read the asphalt article and understand it better (re: my email to you a few minutes ago). I can’t quite get where More’s Landing was – since More Ranch Road leads to the Gas company and that is all cliffs – why would they use More Ranch Road and did it used to go over to the Goleta Beach or mobile home park area? Thank you for your great articles!

Actually, I think the old pier was right at the end of Anderson Lane! It went straight out from Hollister.

Very cool. I love your history posts, Tom!

Thanks Dannon!

Wonderful info. My Grandfather George R. Willey worked as a mine hoist operator for several year around 1895s. Was later called upon to locate old mine shafts when a fire fighter fell into one after UCSB (my alma mater) occupied the mesa.

Wonderful history. Thanks for sharing.

Where exactly on campus is this?

Sorry, UCSB has asked we don’t publicize the exact location for safety reasons.

Hi Tom, Nice article on the asphalt industry. I really like all the articles you write and how you present them. So interesting! I had no idea there had been a mine at Campus Point, but then, isn’t it called Coal Oil Point, so no surprise, I guess. Was this the asphaltum deposit known as La Patera? I’m researching the Alcatraz Mining and Asphalt Company and trying to come up with an initial date. I can’t find them before 1895, but you mention 1890, can you give me some help on the source of that information? It’s actually for a small section for an article on William Henry Crocker in SB. Thanks for any help!